A Request

I am uneasy, and I don’t know why. I imagine that is why I am uneasy.

We are in my study for the evening read: Thalia, Jini, the fairy, Johannes, and the brownies (out of sight). There is an air of tension between Thalia and Jini; they are all business. There hasn’t been a giggle passed back and forth.

In Thalia’s hands is my copy of Myths and Folk-Lore of Ireland, by Jeremiah Curtin. I have rarely seen her reading it.

“Tonight’s tale,” Thalia announces, “is The Three Daughters of King O’Hara.”

The eldest daughter of King O’Hara decided how she would marry. She put on her father’s cloak of darkness and wished for the most handsome man in the world. He immediately appeared in a coach pulled by magnificent horses and whisked her away. The second daughter did the same, settling for the second-most handsome man.

These men came with a price. Being enchanted, they could spend either the day or the night as men, and the other half of the time as seals. Their wives had to choose, and both preferred they be men during the day.

The youngest put on the cloak of darkness and wished for a white dog. Appearing in a splendid coach, a white dog whisked her away and offered a similar condition as had been offered to her sisters. She chose he be a dog during the day and a man at night.

They had three children, two boys and a girl, who were carried away by a gray crow a week after their births. The white dog had forewarned the princess not to shed a tear over the loss, but she cried one tear over the girl, a tear that she caught in a handkerchief.

King O’Hara, at first angered at his daughters leaving him, reconciled with them and offered a feast. The husbands were welcome, but the king did not wish to entertain a dog. However, the youngest insisted.

The queen that evening, in the company of the cook, snuck into her daughters’ bedrooms to find the youngest with a most handsome man and the others sleeping with seals. Unfortunately, she also found the dog’s skin and threw it into the kitchen fire.

The husband of the youngest daughter began his flight to Tir na n-Og after explaining that had he been able to stay under her father’s roof for three nights with her, the curse over him would have been broken. She followed him, and the next three nights he instructed her to stay in certain houses, in each of which she was hosted by a woman, met one of her children, and was given magical gifts: a scissors, a comb, and a whistle. However, her daughter had only one eye. The princess restored the other eye with the tear she had caught in the handkerchief.

On the fourth day, the husband explained she must not follow him, for having lost his dog form, he must now marry the queen of Tir na n-Og. The princess hesitated a while but eventually followed.

She was befriended by a washerwoman and used the scissors and comb to benefit the children of a henwife. However, the henwife warned the queen of these two magical gifts. The queen demanded them, and the princess traded them, each in turn, for a night with her husband. This the queen granted, but she drugged the husband.

After those two failures, the princess used the whistle to call the birds. From them, she found out what she must do. The queen found out about the whistle and wanted it as well. On the third night, the princess left a letter with her husband’s trusted servant, telling her husband what they must do to kill the queen.

In front of the castle grew a holly tree that the husband then cut down. Out of the tree sprang a sheep. The princess released a fox that ran down and tore open the sheep, from which flew a duck. The princess released a hawk that downed the duck, smashing the egg inside the duck. The queen’s heart, hidden in the egg, broke, and the queen died.

They held a great feast, the washerwoman and the servant were rewarded, the henwife burnt alive in her house, and the princess and her husband reign in Tir na n-Og until this day.

Thalia closes the book, glances at Jini, raises the book and stares directly at me. “Will you take Jini and me to Miss Cox’s garden to meet Mr. Curtin?”

Ah, that’s the uneasiness in the air. Will I let Jini visit the garden?

“Of course I will.”

They giggle.

Fairy Tale of the Month: June 2023 The Three Daughters of King O’Hara – Part Two

A Meeting

It is a gorgeous June day in Miss Cox’s garden. When we left the house, a fine drizzle filled the air, but not here. A bench and two chairs surround a small round table, all of wrought iron. On the table sits a larger-than-usual teapot in its cozy and four china cups. How does Miss Cox know what to anticipate?

Our eyes, trained on the garden gate, soon gaze upon an elderly man with a somewhat scraggly beard and sad eyes. Yet his countenance has a merry tone. This is a man who has seen the world and found peace with it.

“Mr. Curtin,” I say, “Let me introduce my granddaughter, Thalia, and her dear friend Jini.”

He nods his greeting, sits, and Jini springs up to pour the tea. Thalia, prepared with a script in hand, starts the interview. “Mr. Curtin, Jini and I are particularly interested in The Three Daughters of King O’Hara. How did you come to write it?”

“To be clear, I did not write it, I collected it. Oh, I did translate it from the Gaelic language through an interpreter. Although I am born of Irish parents, my specialty ended up being Native American and Slavic languages. I am fluent in many tongues but not Gaelic.

“I worked for the Bureau of American Ethnology as a field researcher and did much work on Native American culture and their stories. I have also translated literary works from Slavic languages. Eventually though, my Irish heritage called to me. My wife, Alma, and I visited Ireland a number of times to collect stories.

“We were afraid many of the older tales we had come to collect may have died out. We found that not to be true, but the tales survived only among the Gaelic speakers, that is, the areas where Gaelic was the everyday language, such as the Aran Islands. We did not collect a single tale from an English speaker. The tales we collected were totally tied to the Gaelic language.”

Thalia nods and refers to her script. “Jini and I were attracted to the youngest daughter. We liked her pluck. What attracts you to tales like this one?”

“A tale may be considered a thing of value from three different points of view. From one point of view, it is valuable as a wonderful story and the way in which this story is told. A beautiful tale has a value all its own.

“From a second point of view, a tale is interesting for the social or antiquarian data that it preserves or for purposes of comparison with tales of another race. This is the folklorist approach.

“From a third, and very small class, a tale is valuable for the mythical material it contains, for its contribution to the history of the human mind.

“As for myself, it is hard not to hold all three points of view at once. I am charmed by the simplicity and straightforwardness of the narrative. I am titillated by its similarities and differences compared to other tales, and drawn in by the subtle suggestions it makes about the human condition.”

We all take a round of sipping tea before it gets cold.

Fairy Tale of the Month: June 2023 The Three Daughters of King O’Hara – Part Three

A Conclusion

Jini, with a bit of impatience in her voice, pipes up. “Why does she wish for a white dog?”

“Ah!” Jeremiah raises a finger. “Here we return to the point of view of the folklorist, who values the tales for their comparisons. Let me rephrase the question: Are there white dogs in Celtic myths and legends? The answer is ‘yes.’ There are a number of them.

“I’ll skip over the hounds of hell—white dogs with red ears—and go straight to Bran and Sceόlang (Raven and Survivor), the hounds of Fionn mac Cumhail. Fionn’s aunt, during the second of her three marriages, is turned into a dog by her unhappy mother-in-law. She gives birth to two white hounds before returning to her human form. The dogs, keeping their canine shape, are given to Fionn; Bran and Sceόlang actually being his cousins.

“In a work known as the Book of Invasions, there appears a poem about a creature that is a sheep by day and a hound at night, and what water touches the creature turns to wine.

“I should also mention Cuchulain, the hero of the Ulster Cycle, whose name translates as ‘Hound of Culann.’ He does not turn into a dog, but does become monstrous in battle.”

“Wait. They aren’t exactly the same as the princess’s white dog,” Thalia questions.

“No, but they are comparable. That is what interests the folklorist.”

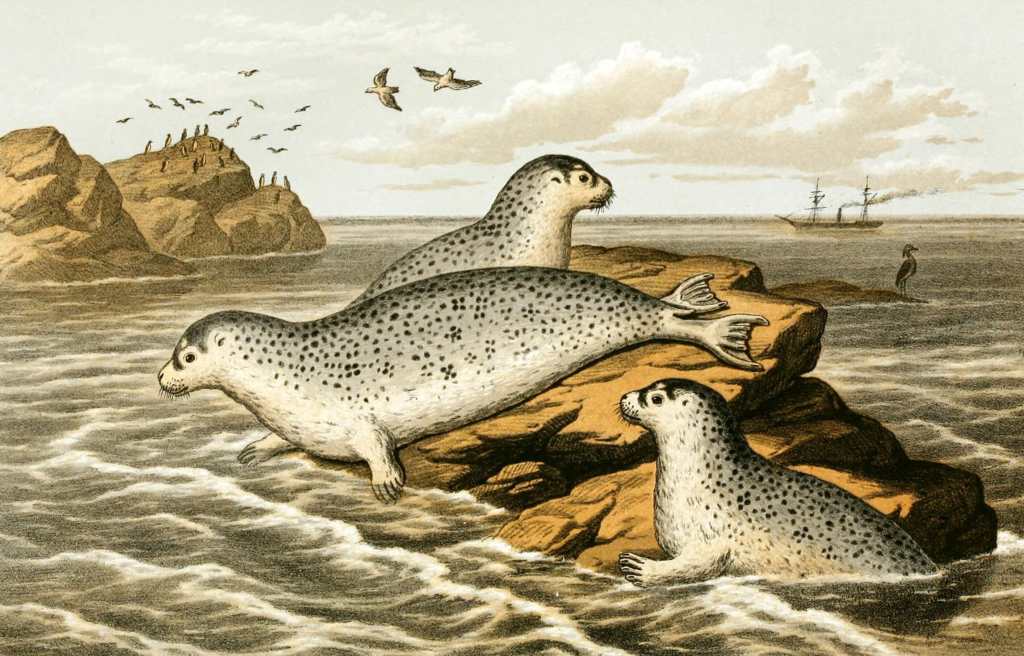

“And the seal thing?” Jini wants to know.

“Selkies!” Thalia chimes in.

“Quite right,” Jeremiah acknowledges. “There is a long tradition about the people of the sea, who are shapeshifters. They can be seals in the water and humans on land by removing their sealskins.

“A typical selkie tale is about a fisherman who sees a female selkie, or a group of selkies, in human form, and steals a sealskin, forcing its owner to marry him. They have children and are a family until she rediscovers her sealskin, puts it on, never to return, abandoning the children and her husband.”

“Oh, how sad,” Jini pouts.

“Again, not exactly the same as our story,” Thalia observes.

“And the thieving gray crow?” Jini asks.

Mr. Curtin hesitates. “It almost has to be Queen Eriu or Erin, from whose name the word ‘Ireland’ is derived. She was one of the last three queens before her people, the Tuatha Dé Danann, were driven into the fairy world, Tir na n-Og. The other three queens were her sisters, all married to three brothers. As a shapeshifter, her form was that of a gray crow. There are many crows and ravens in Celtic mythology, but no other than Eriu’s form that I know of is described as a gray crow.

“If the gray crow in our story is a reflection of Eriu, and the three women who take charge of the princess’s three children are she and her sisters, then the irony is that these women give the princess the magical gifts that become the instruments to trap and destroy the queen of Tir na n-Og.”

“Wow,” says Thalia.

“I can’t help but think,” I say, “that the motifs of the white hounds, the selkies, and Eriu were thrown into a caldron by the storytellers, heated up and blended, reemerging to appeal to a different palate.”

“That is not a solid folklorist analysis,” Jeremiah smiles, “but you may be right.”

Your thoughts?