The Quern

The bell above Augustus’s tobacco-shop door announced my arrival. He looks up from his newspaper as he stands behind the counter.

“What will it be? Leprechaun Gold, Old Rinkrank?”

“No, I haven’t had Black Dwarf for some time. I will take two ounces of that.”

“Black Dwarf was the first of my blends you bought, you know. But see here, I’ll not sell it to you until you tell me a story.” Augustus smiled.

“Well, don’t I always? Actually, the girls have decided that on Christmas Eve, after the holiday lasagna at Melissa’s, we all must choose a story to read.”

“Ah, that sounds like the start of a fine tradition. What story will you choose?”

“One I found in Fairy Tales From the Far North.”

“P. C. Asbjornsen,” Augustus fills in.

“Quite. It’s called Quern at the Bottom of the Sea.”

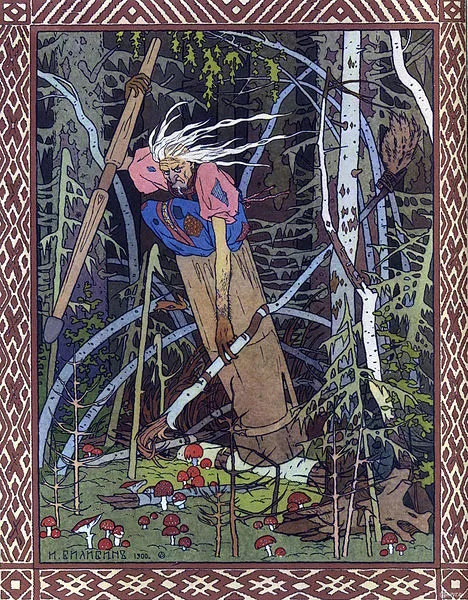

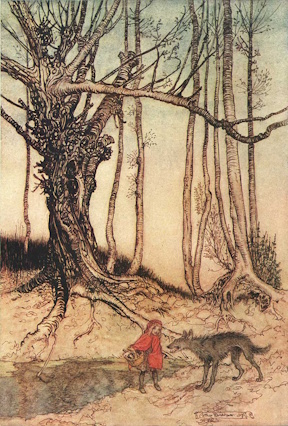

There were two brothers, one rich and one poor. The poor brother came begging on Christmas Eve for food for his family. Ungraciously, the rich brother threw him a ham, saying, “There it is; now go to the devil.”

Hearing this, the poor man went off to find the devil. And he did.

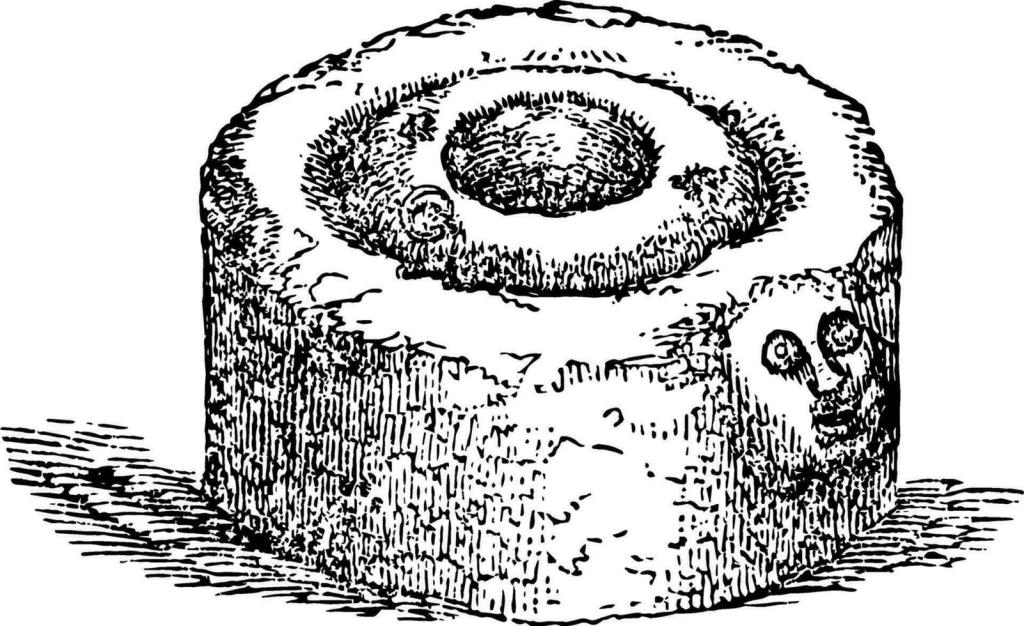

Outside of the devil’s house was an old, bearded man chopping wood, who informed the poor man that the devil was in want of a ham, but the poor man must trade for it and get the quern, the hand mill, stored behind the door.

The devil was reluctant to trade, but eventually he did. The old man explained that the quern would grind out anything he wanted and instructed him on how to stop the quern.

Before midnight of Christmas Eve, the poor man returned home to have the quern produce a feast for his family, complete with a tablecloth and candles. On the third day, he invited all of his friends to feast as well.

The rich brother, jealous of his brother’s good fortune and knowing his brother had nothing to eat a few days before, demanded an explanation. After a bit too much drinking, the poor brother let slip his secret.

The rich brother now demanded that the poor one sell the quern to him. The purchase was put off until harvest, giving the poor brother time to put by all the stores of things he would ever need. When he handed the quern over, he purposely did not tell his brother how to turn it off once started.

The new owner of the quern asked for broth and herrings for breakfast. Dutifully, the quern produced it in abundance. His kitchen soon filled with broth and herrings, and he, shortly, was flushed out of his house on a wave.

If the whole parish was not to be drowned, he needed to go back to the poor brother and beg him to take back the quern. This the poor man did for an additional amount of wealth.

With the quern back in his possession, the now-not-so-poor brother put it to better use. He bought a large farm and went so far as to plate the house with gold. That attracted much attention. He was eventually visited by a skipper/merchant who offered him a great sum for the quern. It was sold to him, but again, without much instruction.

The merchant traded in salt. Instead of travelling to distant lands to buy salt, he simply carried the quern onto his ship and had it grind out salt. Salt soon filled the hull of the ship and every square inch of it until the ship sank.

The quern now sits at the bottom of the sea, churning. That is why the sea is salty.

Augustus nodded his head knowingly.

Part Two

Pourquoi Tale

“A pourquoi tale,” says Augustus. “I didn’t see it coming. But wait, it is ringing a bell in my head.”

Augustus darts upstairs to his library. He is no sooner out of sight than the bell over his door rings. I explain to the customer that Augustus will be back shortly, but might I help him? Well, I know Augustus’s stock pretty well.

I talk him into trying out Elfish Gold, one of my favorites. I am weighing out two ounces when Augustus returns, raising an eyebrow at his new assistant. After the transaction is complete and the customer is gone, we settle in chairs behind the counter.

In his hand is a copy of the Prose Edda, which is at least in part by Snorri Sturluson. “I will guess the origin of your tale is the piece called The Song of Grόtti.

“King Frόŏi bought two enslaved giantesses, Fenja and Menja, and chained them to his magical mill, Grόtti. The king had them grind out gold, peace, and happiness, augmented by their singing. He gave Fenja and Menja no rest, and in revenge, they sang a different song and ground out an army led by a sea-king named Mysing, who defeated King Frόŏi and seized Grόtti and its two slaves.

“Mysing was no better a master, but now they were on a ship grinding out salt. When the ship sank, Grόtti ended up at the bottom of the sea, run by a whirlpool.”

I fill my pipe with some Fairy’s Favorite that Augustus offers me.

“Hmmm,” I say, “no devil, no brothers, yet obviously the two tales are related.”

“Yes.” Augustus lights his pipe. “The Prose Edda was compiled in the thirteenth century, hundreds of years after Christianity had established itself in the North, but the tales are certainly from pagan times. There is no Christian gloss upon them.”

“You suggest,” I say, “that The Song of Grόtti pre-dates my tale?”

“I’ll wager my meerschaum on it!” he replies, holding up his favorite pipe.

“I won’t challenge you,” I easily concede. “But let me ask, are all fairy tales derivative? Do fairy tales always borrow—no, I’ll say steal—their themes and ideas from myth and legend? I want to say ‘no.’ I’ve always argued that myths, legends, and fairy tales—if inspired by something historical, like King Arthur—really draw from the collective unconscious, our dreams, our group wish/ideal for their content.”

Augustus puffs hard on his pipe, considering the thought. “I must come down on the theft notion. The myths and legends were, I suspect, developed by the bards, or their like: skilled, educated, trained individuals.

“Fairy tales are of the illiterate lower class, told in taverns or around the home hearth to equally uneducated listeners, not people of the court whom the bards entertained.”

“The French court was interested in fairy tales,” I defend.

“Well, of course, Charles Perrault, Madame d’Aulnoy, Henriette-Julie de Murat, but that was an affectation, a fad; it does nothing for your position on fairy-tale origins.”

I really hate it, at times, when he is so much smarter than I am.

Part Three

Purposefully Vague

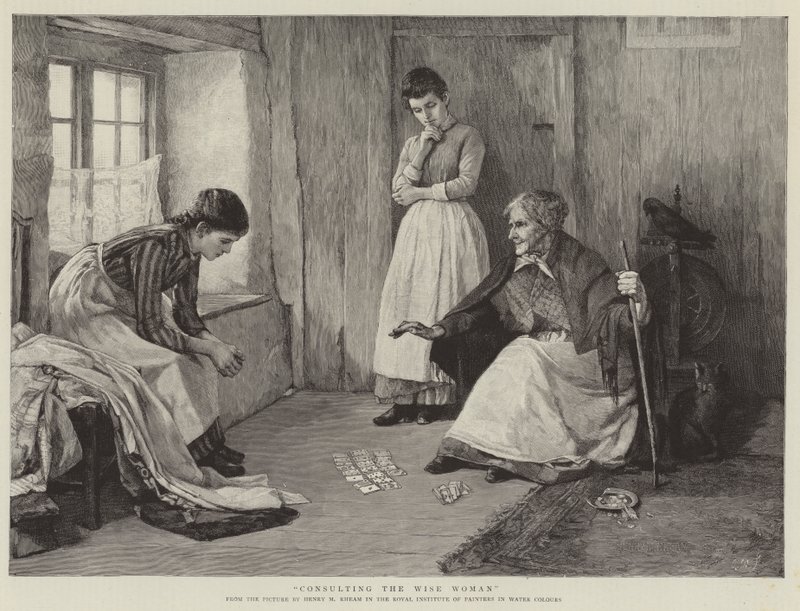

I do love Melissa’s Christmas lasagna. Paired with garlic toast, it’s a wonderful winter’s repast.

Sated, we now sit in her drawing room—as she likes to call it—Melissa and I with glasses of merlot and the girls with their Cadbury hot chocolate. We have finished reading our stories to each other. Following the tradition of Victorian Christmas “ghost” stories, Melissa favored us with The Cat on the Dovrefjell, Thalia with Gabriel Rider, and Jini with her favorite part of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol,it being the visit of the third spirit, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Mine had the least to do with Christmas, but they all got to roll their eyes at the ending.

“Wait a minute,” Thalia critiques, “if the devil wanted a ham, why didn’t he ask the quern for one, or a few for that matter?”

I wag my finger at her. “Haven’t I raised and taught you not to apply logic to fairy tales?”

Another rolling of the eyes with a giggle from Jini in the background. “Yes, but this one is a little too much from the start. And why did neither of the brothers ask for gold from the start?”

“Ugh, and herrings for breakfast!” Jini wrinkles her nose.

“Well, they were Norwegians,” I say, my attention drawn to a plate of shortcakes on an occasional table.

Perhaps,” Melissa suggests, “Norwegians think of their stomach before considering other things. However, what I liked in the story was the poor brother’s development. He is presented to us as a simpleton. When his brother tells him to go to the devil, he takes the words at face value, and with the luck of a fool, he finds the devil.

“Later, when the rich brother strong-arms him into selling the quern, the poor brother does not tell the other all that he needs to know. Further into the story, when he resells the quern to the merchants, he obviously anticipates his doubling of profit once more. Things did not happen that way, and now we have a salty sea, but it shows he was thinking.”

“Huh,” I say, “interesting. For me, I thought his character was being inconsistent. He is at first poor and stupid, then, suddenly, clever and rich. I didn’t see a progression.” I nibble another shortcake.

Melissa sips her wine, considering. “The fairy tales are, perhaps purposefully, vague. That might be one of their strengths and not a fault. You see the main character as being inconsistent, and I see him as coming into his own. You and I—and everyone else, present company included—project our notions onto the tales. What I see in the story is not what you see. We are interpreting, just like we interpret our dreams. I am not sure any other genré allows us that much latitude.”

“Wow, I didn’t get any of that.” Jini is looking a little wide-eyed. “I got Thalia’s point after she said it, but I never would have thought of it. I guess I don’t want to analyze the tales. I just want to hear them and let them wash over me. They make me feel happy and sad. I think that is all I want them to do.”

That’s simple enough.

Your thoughts?