Twelve Heads

We don’t have as many evening reads as we did when Thalia was little. In fact, the pattern has settled into readings on Sunday nights. A good way to start a week. Thalia, some time ago, took over the duties of being the reader. I enjoy being read to, and Thalia has such a soothing, yet articulate voice.

We have all gathered as usual, Thalia and I in our comfy chairs, Johannes curled up on the window seat, the fairy on Thalia’s shoulder, and the brownies lurking in a dark corner.

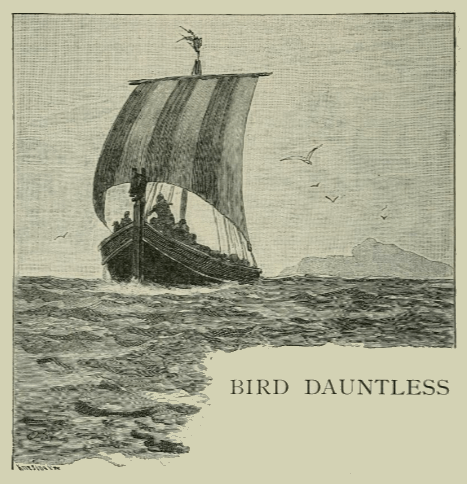

Thalia holds a new acquisition in her hand from Melissa’s bookshop. “Fairy Tales From the Far North, by P. C. Asbjornsen,” she announces. “From which I will read Bird Dauntless.”

There is a king with twelve daughters, of whom he thinks the world, but one day they disappear. Word of this strange event comes to a realm whose king has twelve sons. The brothers determine to find and marry the twelve princesses. Their father gives them a ship with Knight Redbeard to command and steer.

They search for seven years until they encounter a storm that lasts for three days. At the end of it, all are so exhausted that they fall asleep, except for the youngest prince. He sees a dog on an island and lowers a boat to rescue it. The dog leads him to a castle, and turns into a beautiful maid, with her father, a fearsome troll, sitting beside her.

From the troll, the prince learns that the twelve princesses were stolen away by the troll’s master/king to scratch his twelve heads. The troll gives the prince a sword with which to slay his master/king, allowing the troll friend to be the new king. The troll says there is still another seven-year journey before them in order to get to their destination. The troll also warns that Knight Redbeard hates the prince and will kill him if given the chance.

After seven years, the pattern of the three days of storm repeats, and the youngest prince slips away from the ship as the others sleep, enters the castle of the twelve-headed troll, and finds him asleep as his friend, the troll, had predicted. He waves the princesses to stand back and quickly slays the king troll.

Having already started their return voyage, the princesses realize they have forgotten their crowns. The youngest prince offers to return for them while the rest remain at sea. The Knight Redbeard takes the opportunity to abandon the prince with threats of death for anyone who defies him. The prince is left stranded on the old troll king’s island.

To the prince’s aid comes the Bird Dauntless, an apparent resident of the old troll king’s palace. It flies him back to the new troll king’s palace—the prince’s friend—with magical speed.

Seven years later, after a three-day storm, the sleeping crew comes to the new troll king’s island. The youngest prince boards the ship, reclaims the sword of the new troll king for him, and sees that the youngest princess sleeps with a naked sword by her side and that the Knight Redbeard sleeps at her feet.

Another seven years pass as the crew travels back to the kingdom of the twelve princesses’ father. Toward the end of the seven years, the new troll king gives the prince an iron boat that will take him back and return by itself. When the prince comes in sight of his brothers’ ship, he raises an iron club to evoke a storm that allows him to pass by them unnoticed.

Pretending to be a storm-tossed sailor, the prince creates the rumor (however true) that the princesses are returning. When they do return, there is much joy except for the youngest princess, who is now obliged to marry the Knight Redbeard.

The prince, now pretending to be a beggar, offers up the crowns. Seeing this, the youngest princess reveals the deceit of the Knight Redbeard. The king has Knight Redbeard executed before he can do any more harm.

“And all, as you may suspect,” says Thalia, “live happily ever after.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: June 2024 Bird Dauntless – Part Two

Twenty-eight Years

“Twenty-eight years!” Melissa marvels. “Seven to the troll’s island, seven more to the king troll’s island, and fourteen more returning. What a patient people they must have been.”

I smile at her quip. “This is the stuff of fairy tales.”

We are sitting, again, on Melissa’s reading-space couch. She has generously provided a full teapot and cups.

“Obviously, you know the story,” I say.

“I read the book before I sold it to Thalia. That is one of the perks of being a bookseller. I read them before I sell them to my profit.”

“Very good,” I say. “But what are your thoughts on this tale?”

“Well, first is the twenty-eight-year saga.” Melissa holds her teacup to her mouth but does not drink, frozen in thought. “There is a cultural context to this tale that came out of the Middle Ages. The peasantry was tied to the land. They existed pretty much from hand to mouth. It was a mark of privilege to have the ability to travel. Besides religious pilgrimages, there were the Crusades. That men of royalty would go off for extended periods of time seemed to have been expected. Twenty-eight years is still excessive, but for the listeners of the time, not unimaginable.”

She finishes taking a sip of tea and continues.

“Then there is the strong suggestion that none of the characters age.”

“No, wait!” I exclaim. “The story does not say that.”

“You are right; it does not, but it is implied. Note that the heroes and heroines get married and live happily ever after. ‘Ever after,’ not ‘for the rest of their lives.’

“Death in the fairy tales is reserved for three categories of characters: witches, trolls, giants, and all other evildoers; kings that are old when the story starts so that the hero can inherit the kingdom; and mothers so that their progeny can have an evil stepmother. There is the caveat that if the king gives half his kingdom to the hero, he can avoid mention of his demise. Even taking an axe and cutting off the head of a fox may produce the enchanted brother of the heroine. Death is a bit elusive in the tales.”

“I am going to suggest you are exaggerating.” I sip my tea.

“Let’s take our tale,” Melissa persists, pouring herself another cup. “Our heroes and heroines return on the cramped quarters of a ship for fourteen years, at the end of which there is no mention of children being born during that time.”

Oh, she may have a point here.

Melissa takes another sip of tea. “They don’t get grumpy, there is no mention of graying hair, there are no medical issues. Why? Because they are suspended in time.”

“Now there is a notion I have not entertained before.” I set down my teacup. “Time often moves differently in the Celtic fairy world than it does in our world. Why shouldn’t it not move strangely in other tales as well? I will buy into your analysis.”

Melissa smiles. She has her little victory.

Fairy Tale of the month: June 2024 Bird Dauntless – Part Three

So Many

“There is also quite a cast of characters.” Melissa absently rotates her teacup with her fingers. “This tale starts with twelve princesses, twelve princes, and their two fathers.”

“That’s twenty-six,” I say.

“Then there is the Knight Redbeard, two trolls, one troll daughter, and the Bird Dauntless.”

“Making an uneven thirty-one,” I calculate. “Unless we count the king troll’s twelve individual heads.”

“No, don’t.” Melissa smiles and takes another sip of tea. “Eleven of the princesses and eleven of the princes are a sort of corps de ballet, dancing around in the background, not coming front and center. Only the youngest prince and princess do we actually see.”

“Hmmm, a form of crowd control?” I say.

Melissa ignores my quip. “Out of the thirty-one characters, only two have names: the Knight Redbeard and the Bird Dauntless.”

I raise a finger. “Knight Redbeard I recognize. In the Danish folk tales with which I am familiar, he is the Red Knight, the stock villain. He is in the story to cause trouble, sometimes only for the sake of causing trouble.”

“I recognized him too. He is the one to be punished by death at the end of the tale and is brought back again in another tale to be killed once again. I must wonder if this was not a running joke among the tellers to recycle the bad guy.

“What I found most curious was the Bird Dauntless, starting with that curious name. Asbjornsen thought it important enough to name the story after it. The bird is a necessary component of the tale. The young prince would otherwise remain abandoned. Nonetheless, the bird only has a brief appearance and then disappears from the tale.”

“I have,” I say, “run across large birds rescuing heroes before. What jumps to my mind, for example, is The Underworld Adventure. In that story, the hero is abandoned by his two brothers when they are looking for missing ladies in an underworld. It is a huge bird that flies back to the upperworld, similar in feel to our tale. There, too, the bird serves its purpose and then is gone.”

Melissa considers this while drumming her fingers. “I suppose it is not unusual for characters to disappear from these tales. Besides the Bird Dauntless coming and going, the princes’ father gives them a ship, and then the story is done with him. We don’t even hear him being invited to the wedding. I also think the troll’s daughter got left behind—a beautiful maiden and shape-shifter—the story could have done more with her for my liking.”

“For myself,” I say, “I found the use of the three-day storm an interesting device. Every time the ship comes to one of the troll islands, their arrival is preceded by a storm, after which the crew falls asleep except for the youngest prince, who forwards the story.

“On the return trip, he raises an iron club, given to him by his troll friend, to create a storm so that he could slip by them unnoticed. I don’t recall ever seeing a troll/storm relationship before.”

“Let me return to the character of the bird,” says Melissa. “What of the name ‘Bird Dauntless?’”

“I did Google search that,” I say. “I came up with nothing.”

Your thoughts?