Three Boys

Today is the last Monday in May, which means it is the Late May Bank Holiday. The Early May Bank Holiday, with its Maypole dancing, has come and gone. Today is simply a day to visit with friends.

I have invited Duckworth and Melissa over, and I know how much they both enjoy espresso. I am on my way to the third floor to retrieve the machine from storage. It should only take a moment. I know exactly where it is. It is the first room on the left when I come up the stairs. I keep all the electrical devices in storage there.

Up the stairs I go, into the room, grab the espresso machine, and step back into the hallway.

Except it is no longer the hallway.

I am in a large, barren room containing only one chair, in which is seated an old woman, the same old woman I encountered the last time I came for the machine. I guess I should have known better.

I approach her, sit down at her feet, the espresso machine in my lap, and wait for the story.

An evil queen poisoned her husband, the king, so that she would rule until her son came of age. When he did, she searched for brides of whom she approved, but her son married one not of her choosing.

Three times, the young queen, while her husband went off to war, gave birth to a beautiful boy, all of whom were whisked away and an animal substituted: a puppy, a piglet, and a kitten. After the third, the evil queen had the young mother drowned, falsely accusing her of adultery.

While the evil queen tried to find her son a new bride, he became despondent and reclusive, still devoted to his departed queen.

Years later, when he lost his way during a hunt, he came across six lads playing by their father’s mill. Three of them were taller and more handsome than their siblings and bore a resemblance to him and his wife.

The king observed that when one of these three boys went to wash his muddied hands, he walked down to a stream and not to the nearby well. When the king asked him why he chose the stream, the lad answered, “I go down there instead of the well because the water in the well rushes away from under my mother’s feet.” When the king asked, “Where is your mother?” the lad answered, “In the water.”

Later that day, the other two lads, who went to the stream, one to wet a thread for a needle and the other to wash his ball, gave identical answers to the king’s questions. Yet, the miller’s wife declared these were all her children, whom she loved equally.

In the evening, the king returned to the stream and followed a light until he could go no farther and fell asleep. In the morning, he awoke hearing a splashing noise. Parting the branches of a thicket, he saw his wife sitting on a branch, churning the water with her feet.

Overwhelmed with joy, he listened as she explained how his mother had abandoned her to starve and freeze to death, but the wood sprites adopted her, feeding and clothing her so that she could move her feet in the water to keep it from freezing.

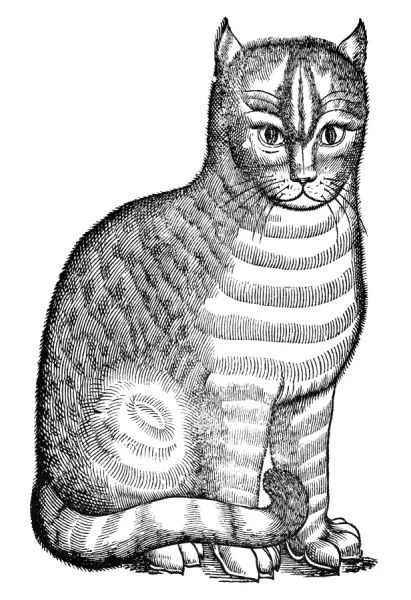

With the king’s rediscovery of her, she is reunited with her children as the wood sprites promised. The miller’s wife revealed that the children were found floating down the stream in boxes as each of her three children was born and made no further claim on them. She also pointed out that each of these children had a tattoo: a dog, a pig, and a cat.

The story concluded with the evil queen being drawn and quartered.

I find myself sitting in the hallway, clutching the espresso machine. I dart for the staircase before anything else happens.

Part Two

Drinking Espresso

While the espresso machine steams and gurgles, I tell Duckworth and Melissa the tale without telling them where I heard it. Duckworth is unaware of my connections “beyond the veil.” Melissa is a participant.

“You are, of course, referring to Schönwerth’s book The Turnip Princess, edited by Erika Eichenseer, to be more exact.” She glances from Duckworth to me. She knows about my third-floor experiences. “If I recall, this particular tale is The Mark of the Dog, Pig, and Cat.”

“Of course,” I say.

I bet she’s right.

Duckworth’s eyebrows rise in delight when he sips his espresso, but frowns when he says, “Sorry, that tale did not make much sense to me.”

Melissa gives him a small smile. “I am not surprised you say that, but it is a quintessential fairy tale.”

Duckworth scowls. “Hanging around with this guy,” Duckworth motions toward me, “I’ve heard a number of Grimm and Lang tales. This one doesn’t hold a candle to them. It is full of nonsensical things.”

Melissa shakes her head. “Franz Xaver von Schönwerth was a true collector and not so much an editor as were Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm and Andrew Lang—actually Andrew’s wife Leonora, who also translated tales for the Colored Fairy Books.

“The Grimms, over their numerous editions of Children’s and Household Tales, often rewrote some of them, making substantial changes. Schönwerth did no such alterations that I know of.”

Duckworth has folded his arms. “Well, does that make it any less of a fairy tale?”

I see the signs of annoyance in Melissa’s eyes as she sips her espresso before answering. “It makes them literary fairy tales, not folk fairy tales. In my mind, a true fairy tale has no known author. Charmingly, the marks of a folk fairy tale are its inconsistencies, shaky structure, surrealism, and unexplained elements.”

“Wait,” Duckworth protests. “Haven’t you just described a bad story?”

Melissa sighs as Duckworth warms up to his argument. “For example, at one point in the story, the young queen is drowned by the evil queen. Later, the young queen says the evil queen abandoned her to starve and freeze to death. Which is it?”

Melissa rolls her eyes and does not answer.

“Further,” he says, “the story starts with the queen poisoning her husband and quickly moves on, skipping over what should be the inciting incident. Why is it even there? It doesn’t forward the story.

“And talk about surreal, the young queen spends years with her feet dangling in cold water. Then there are the animal tattoos. What’s that all about? Where did they come from?”

“Magic!” Melissa almost aspirates on her espresso. “The fairy tales are about magic. Don’t apply reason. Don’t apply literary structure. Don’t try to fit them into the commonplace. Don’t reduce them to the easily understood.

“The true fairy tale is meant to catch us off guard, get a little bit under our skin, pull us away from the normal, the expected, and into the uncanny.”

“Sorry,” says Duckworth, “makes for a poor story.”

Melissa rests her forehead on her hand.

Part Three

Tantalizing Metaphors

I decide to interrupt their argument with a question that has aroused my curiosity. Why the old woman told me this story, I have no idea, but there are tantalizing metaphors to explore.

“Let me ask,” I say a little loudly to redirect their attention, “despite the story’s incoherence, there is an undercurrent in the tale dealing with water and the young queen’s feet. I mean no pun when I say ‘undercurrent’ when we are talking about water. It is simply the right word.”

“No punishment is required,” Duckworth comes back.

I will let him get away with that.

“What were the words again that the lads say?” Melissa asks.

“I quote, ‘I go down there instead of the well, because the water in the well rushes away from under my mother’s feet.’ And when asked where their mother is, they reply, ‘In the water.’”

“Yeah,” Duckworth confesses, “I didn’t get that at all.”

Melissa clutches her cup and takes another sip. “I am reminded of the Grimms’ Three Little Men in the Wood, where the young queen is drowned by her evil stepmother but returns as a spectral duck to reclaim her position among the living.”

“That is close,” I agree.

“Her feet in the water, though.” Melissa’s intellect drifts through possibilities. “In this tale and the Three Little Men in the Wood, the good queens appear to have died but are resurrected by their husbands’ actions.”

“That’s getting a little too messianic, don’t you think?” Duckworth complains.

Melissa presses on. “Whichever way our young queen died, she was a victim of the elements from which the wood sprites spared her. To me, she is in some sort of limbo, although she is guiltless of any sin.”

“She is splashing the water to keep it from freezing,” I remind.

Melissa raises a finger. “We should consider the miller, who needs the water to flow to run his mill, he and his wife being the protectors of her children.”

“Ah!” I say. “And there is a connection between his boys being born and him finding the babies in the stream. I wonder if we are to infer the wood sprites had a hand in that?”

“I will guess so.” Melissa sips a bit more espresso, although it must be cold by now. “The sprites told her she would be reunited with her children. They at least knew about the children and appeared to know the future.”

“The future,” I add, “that we see played out in the story when the king followed a light by the stream, fell asleep, and awoke to find his queen. There is something significant in that process of finding her. He too went through some sort of transformation, at the end of which he could release his wife from her ordeal and bring her back among the living.”

“The tattoos,” Melissa muses, “I will attribute to the wood sprites as well. They are the magic in this story. In any case, the tattoos simply provide more evidence that these are the king and queen’s children.

“What eludes me,” Melissa says as she finishes her espresso, “is the enigmatic response of the lads to the king’s question, ‘…the water in the well rushes away from under my mother’s feet.’

“It denotes the difference between water standing in a well and water moving in a stream, but isn’t it the water in the stream that rushes away and not the water in the well?”

Duckworth, who Melissa and I have almost forgotten is in the room, says with a devilish smile, “The Americans have a word for you two. Nerds.”

I accept the moniker with honor.

Your thoughts?