From Russia

Thalia has wished me a good night and gone off to bed. Tomorrow is another school day. She’ll be up bright and early while I linger in bed. I enjoy a late-night read.

At random, I have picked Afanasev’s Russian Fairy Tales off the shelf and am settling into my comfy chair. I turn to a tale with the intriguing title, The Feather of Finist, The

Bright Falcon.

I read, “Once there lived. . . Once there lived. . . Once there lived. . .” My eyes will not move beyond the opening words. I am no longer in my comfy chair. Rather, a seat of red velvet. I am in the front row of an Art Deco theatre, either newly renovated or, in fact, new. I startle to see Melissa sitting next to me in her nightclothes with an identical copy of the book in her lap that is in mine.

She frowns at me. “Is this your fault? I was about to go to bed.”

“So was I,” I lie a little.

Our attention is drawn to the stage as a spotlight shines on a man dressed in the traditional Russian kosovorotka, who says to us, “Once there lived. . .” and proceeds to tell us the tale of Finist.

“A man who has three daughters is in the habit of bringing them gifts when he returns from a journey to town. But all that his youngest daughter asks for is a feather of Finist the Bright Falcon. Whether by fate or by fortune, the father comes across an old man carrying a little box, inside of which is a feather of Finist.

“In her bedroom, the youngest opens the box, and the feather transforms into a handsome prince. She seeks to hide him by releasing him to fly about all day as a falcon and come to her at night. The sisters discover the ruse and put knives and needles at her window.

“The falcon is injured and flees, telling the girl, in a dream, that if she wishes to find him, she must wear out three pairs of iron shoes, break three iron staffs, and gnaw away three stone wafers in her search for him.”

Although I have not looked away, the man has transformed into a young maid wearing a sarafan.

When did that happen?

“In the morning, she sees the blood on the windowsill and starts off to seek her beloved.

After wearing out the first set of iron shoes, breaking an iron staff, and gnawing away a stone wafer, she comes across the hut of an old woman who proves to be a witch but aids the heroine. She gives the girl a silver spinning wheel and a golden spindle that spins flax into gold thread. Also, a ball to follow to the witch’s sister’s house.

“After wearing away the second pair of iron shoes, staff, and stone wafer, she comes to the second witch’s house, where she gets a silver plate and a golden egg, which, when rolled around on the plate, hatches more gold eggs.”

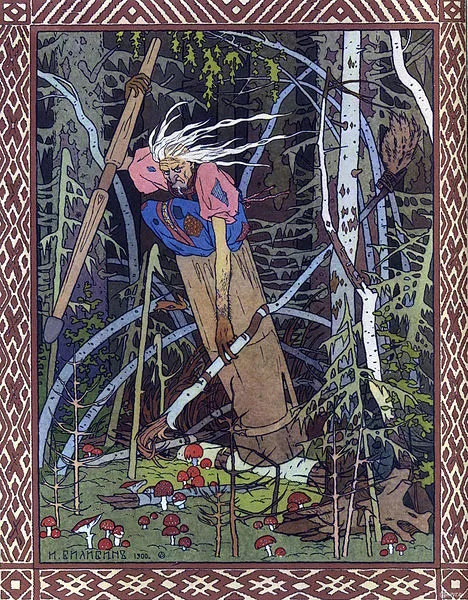

I now see the young maid has become a hag with a large mortar and pestle, as well as a broom, beside her.

“When the third set of iron and stone is worn away, the ball rolls to the third witch’s hut. There, the girl gets a golden embroidery frame and a magical needle that embroiders by itself. The witch also explains that Finist is now married to a wafer baker’s daughter, and that the girl needs to become a servant in the household if she wishes to win her beloved back again.

“She finds that Finist is still in bird form by day and a man by night and does not recognize her. “

I now see a being on stage that is half man and half bird.

“The girl sells the three gifts from the witches for three nights with the husband, but each time the wife drugs him. It is not until the third night that a tear falls on his cheek and awakens him.

“They flee and return to the girl’s home, where, again, she tries to keep him hidden in his feather form. Nonetheless, they attend church disguised as a prince and princess until, this time, the father discovers their trick. The couple is immediately married with a grand wedding.”

The spotlight goes out, and we are in the dark.

Part Two

Maybe Russian

As my eyes adjust, I find myself back in my study. However, Melissa is still with me, sitting in the other comfy chair.

“Oh, what am I doing here!” Melissa is scandalized. Her nightgown is rather sheer. I wander off to find a blanket, pillow, bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon, and two glasses. I assume she will spend the night here. The couch in my study is large and comfortable.

I strike up a fire in the hearth to warm the room as Melissa settles on the couch, modestly covered by the blanket, and cradles her glass of wine.

“I am sure,” she says, “we chanced to be reading the same story, the sort of thing you and I tend to do, and the story took over.”

“And, I am sure,” I say, “the story expects us to talk about it.”

“I,” says she, “will honor the request, although it has inconvenienced me.”

We both smile.

“My first thought,” Melissa sips her wine, “turns towards Beauty and the Beast, as well as East of the Sun and West of the Moon. However, there is no ‘beast’ involved in our tale, although Finist is still an animal husband. There are three sisters in these three examples, who do the youngest no favors. What I am saying is that the youngest sister commands Finist rather than being abducted by him, at least until she loses him.

“There is no pleading to visit her family, as in the other variants. Rather, she dons the iron shoes and tramps off to reclaim her beloved.”

“That,” I say, “is where my mind turns to A Sprig of Rosemary. The heroine loses her husband and travels to the sun, moon, and wind, who give her the gifts needed, which she sells to the bride for three nights with the groom before she can awaken him.”

“Except,” Melissa takes another sip, “it is the three Baba Yagas that hand out the gifts.”

“Wait!” I tap my glass. “Isn’t there only one Baba Yaga, who rides around in a mortar and pestle with a broom, owning a house that walks around on chicken legs?”

Melissa wags her head. “Not really. Not for Russians. For example, a babushka is a scarf that every grandmother wears. Every grandmother becomes a babushka. Babushka means ‘grandmother.’”

“So, every witch is a Baba Yaga,” I come to understand.

“At least in Russia.”

“The Daughter of the Earl of Mars pops into my head as well,” I observe. “In that tale, the male lover is a bird as well. It flees when the king threatens to wring its neck but returns with a flock of birds to defeat him.”

Melissa nods. “Not to mention Cinderella,where she goes to the ball—or in some versions the church—three times in disguise.”

I stoke our fire a bit more. “I can’t call this tale a variant of another story. It appears to be made up from pieces of other tales and yet does not feel pieced together.”

“Or,” Melissa contemplates, “is it the original, and have other tales borrowed from it?”

“Or,” I complicate the matter, “is there another original that all of these are drawing from?”

“I don’t know the answer,” she says, “but I know where the answer is.”

I look at her curiously.

“Lost in the mist of time,” she responds.

I must agree.

Part Three

Maybe Not

Melissa rubs her finger around the rim of her glass, causing it to ring. “I know I harp on feminism when it appears or doesn’t appear in the tales—I hope I don’t bore you with it—but there is another underlying theme in this one.”

“Which is?” I inquire.

“I will call it Christianity being questioned.”

“Oh, that comes up in the Grimm stories as well,” I say. “In fact, as time wore on, Wilhelm edited out some of the less-than-Christian elements and introduced angels into the tales.”

“Yes,” Melissa hesitates. “The brothers were Calvinist, but that has little to do with my thinking.”

“And your thoughts are?” I sip my wine.

Melissa takes a deep breath. I am obsessing over the wafers.”

“The wafers?”

“Yes.” She gives me an apologetic smile. “Allow me to get deep into the weeds.

“First of all, wafers are unleavened bread. Unleavened bread is used for the Eucharist. That the heroine gnaws on a stone wafer as part of her ordeal, and the woman who stole her lover was the daughter of the wafer baker, suggests some sort of parallel between the two.”

“And what might that be?” She is onto something.

Melissa sets her wine glass aside and thinks out loud.

“I don’t need to tell you that we are not dealing with logical events. She cannot wear down three sets of iron shoes in a lifetime. Nor will she break three iron staffs. Gnawing on three stone wafers? Three sets of iron teeth are not part of the deal.

“These challenges are symbolic, of course. The shoes and staffs demonstrate the physicality of her effort and imply the lengths to which she is willing to go.

“The stone wafers are a different matter. Was she sustaining herself on the unsustainable? Was that meant to be as difficult as wearing out iron shoes? Does she move beyond the impossible? Or is there another implication?”

“Such as?” I goad her on.

“Does the story ask us if the Eucharist should not be an ordeal and not simply a wafer that dissolves easily in the mouth? This brings to my mind the Flagellants.’

“The who?”

“The Flagellants, monks who wandered around during the Plague Years, whipping themselves—sinners that they were—praying aloud all in the spirit of penitence. Their religion was not a convenience for them. Gnawing on store wafers was not a convenience either for our heroine, but rather a show of devotion.

“In both cases, whether determination or devotion, we are left to compare the rigors of the heroine consuming stone wafers to the easy life of the wafer baker’s daughter.”

“I think,” I say, “that is an intriguing argument.”

Unexpectedly, Melissa scowls to herself. “Except that I’m wrong. I know a little about the Russian Orthodox, who would be the majority of Christians in Russia at the time, and they used leavened bread in their communion, unlike most other Christian churches. My argument about this Russian story’s relationship to the Eucharist falls apart. Oh well, another harebrained idea discredited.”

We fall silent for a bit.

“Ah!” I say, proud of my revelation. “There was a substantial number of Jews in parts of Russia. The Passover feast demanded the bread be unleavened. Could this be a Jewish tale, making its reference to the Passover bread instead of the Eucharist?”

Melissa is asleep, her wine half drunk, its glass sitting on the table beside the couch. What will Thalia think when she sees this in the morning?

Your thoughts?