Crystal Pyramid

I am returning from an evening stroll in the Magic Forest. I went to the pond and lingered there awhile watching the reflections in the water before going back to my study. It is pleasant to know that every visit to the forest need not end in some sort of drama.

However, as I enter my study through the French doors, there sits on my table by my comfy chair a crystal pyramid about three inches tall. I sit down to inspect it more closely.

Thalia and Jini are away tonight doing who knows what. Melissa, whom I had invited over for dinner, is off to some meeting instead. Duckworth is out of town on some business. Who would have dropped off an odd bauble and left without a word?

Beyond me and the bauble is a table lamp. The light it casts through the pyramid appears as a shifting, shadowy pattern on my side of the tabletop.

Why does the pattern move?

I pick up the pyramid, placing it in the palm of my hand, and peer into its facets, trying to discover the cause.

I now stand in a somewhat exotic, town setting, its architecture not familiar to me. There is panic in the air; soldiers and civilians appear to be scurrying about, but the scenario is frozen.

Without being told, I know what is happening. They prepare to battle; unless they can come up with six hundred thalers for ransom, their enemy would attack. Despite the promise of being made the mayor of the town to anyone who would pay the ransom, no one has come forward. What I am seeing dissolves before my eyes.

Now I am standing by a lake. The tableau in front of me is of soldiers restraining a raggedly dressed youth, as one soldier places coins in the hat of another man who is looking sadly at the youth.

Again, I know what is happening. The enemy has seized a young fisherman, but at his father’s pleading to let his son go, the captain compensates the father with six hundred thalers.

Another scene change, and I am at the back of a crowd gathered around a raised platform on which stand the town dignitaries and the elder fisherman. The scene informs me that the fisherman contributed the six hundred thalers to satisfy the ransom and is being declared the mayor. Further, it is declared that the fisherman will henceforth be addressed as “Lord Mayor” and no other title on pain of being hung from the gallows.

In the next image, I stand behind the young fisherman who is staring at the side of a mountain, which has opened up, revealing an ominous castle. At this point, he has escaped his capturers and has wandered to this spot to witness the miracle before him.

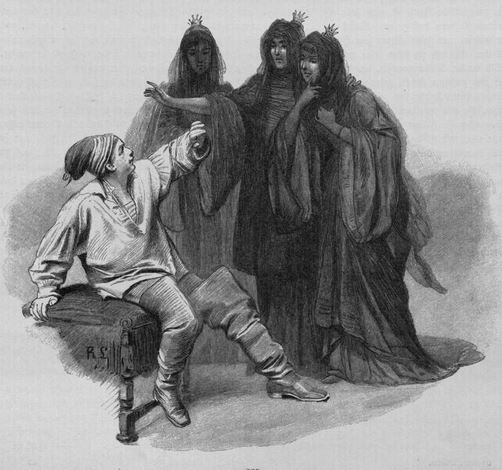

After this scene fades, he and I are inside the castle, in a room where all the furniture is draped in black cloth. Before us stand three princesses, dressed in black and of dark complexion except for a white spot on each of their faces.

I understand they mean him no harm and wish for him to release them from enchantment. He asks how and is informed he must not address them or look at them for a year. If he needs anything, he only needs to ask aloud, and if they are permitted, they will provide. After a time, he wishes to visit his family. He is transported back to his home in East India.

East India?

I now see the young man surround by guards holding spears toward him, along with a group of elderly men pointing their fingers at him.

Upon returning to his hometown, he asks after the fisherman and is told not to use that title for the Lord Mayor, but he persists. The lords of the city are about to take him to the gallows for this offense when he is allowed to visit his childhood home where he dons his old clothing and is recognized by the lords for who he is.

I then see him with his family—dressed in his poor clothing, his father, the Lord Mayor, in rich robes—the father and son embracing one another.

He then relates his story to all. However, his mother warns him against the black princesses and tells him to drip hot wax on them from a consecrated candle.

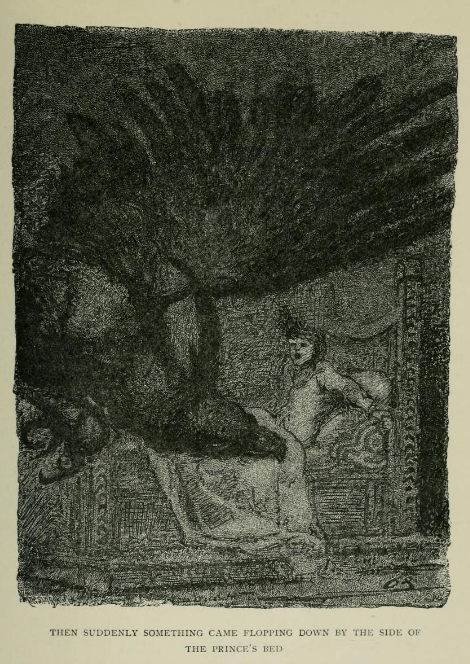

In the next image, he holds a candle above the sleeping black princesses. I know he is nervous and accidentally lets hot wax drip on the princesses. What I see next is more intense. The images flip rapidly, illustrating the actions of the princesses as they turn half white and rise up exclaiming—and I can’t tell you if I heard the words or read them—“You accursed dog, our blood shall cry for vengeance on you! Now there is no man born in the world, nor will any ever be born who can set us free! We have still three brothers who are bound by seven chains, and they shall tear you to pieces.”

In the last scene, the youth has escaped through a window, breaking his leg as the castle crashes into the ground and the mountain closes. There the images stop, my “understanding” ends, and I sit once again in my study staring at the pyramid.

Fairy Tales of the Month: September 2024 The Three Black Princesses – Part Two

On Reflection

My shock increases when I look up and see myself seated across from me in a mirror-image comfy chair.

“What are you doing there?”

“I was about to ask you the same.”

“Well, this is most unusual. I don’t know what to think. I am—permit me to say—beside myself.”

“I knew you were going to say that.”

We regard ourselves for a while until I say, “Well, this is the pyramid’s doing. I’ll suppose it is its way of getting me to think about the story to myself.”

“Agreed,” myself returns. “What do we think about the story?”

“First,” I say, “we know it is the Grimms’ The Three Black Princesses.”

Myself nods. “Certainly one of the lesser tales, but it was in the first edition and not booted out like some of the others.”

“True,” I say. “Perhaps the pyramid wants us to reconsider the tale. I believe we dismissed it when we first read it.”

“True again,” says myself. “Let us tear it apart. We start with a town under siege, the deliverance from which is six hundred thalers.”

“A tidy sum,” I agree, “but if they had passed around the hat, I would think a town full of people, under attack, could easily ante up that amount of money, but that is not the case.”

“Instead,” myself picks up my thread, “the mayoral position is offered up as a bribe, but still to no effect until the fisherman arrives on the scene.”

“And he,” I continue, “acquired the money from the same enemy that had taken his son prisoner but felt somehow obliged to compensate the father with the same amount of money needed to lift the siege.”

“You are thinking what I am thinking,” myself says to me.

“Yes, the economics of this story stink.”

“But let us not be too harsh on this lack of logic. We both know that the fairy tales are not based on logical thinking. In fact, they wallow in defying it.”

“True, again,” I say to myself. “The fisherman becomes the Lord Mayor and is to be addressed by no other title. I can’t help but notice the passive tense of the declaration. The story does not tell us who—the active character—made the pronouncement. It is just there. Subsequently, it is implied that the word is enforced by the ‘lords’ of the town.”

“Good point,” myself nods, “which is a setup for later on in the story.”

“Correct, of course.” On impulse, I reach for my pipe and tobacco and see in my peripheral vision myself doing the same. The study is soon filled with the scent of Angel’s Glory, a blend I keep in reserve for special occasions.

“We now turn our attention,” I say, “to the young fisherman, who has escaped his capturers—they, therefore, gaining nothing for their efforts—and for no apparent reason, is admitted into an enchanted castle.”

“Let’s stop there and linger,” myself declares. “Why does the mountain open up for him?”

“Oh,” I say, “because he is us, or—as we experienced in the pyramid—we stand right behind him. We want the mountain to allow us into the enchanted castle. The fairy tales are always about us, a source of wish fulfillment.”

“I knew that,” says myself, “but I will never tire of hearing it.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: September 2024 The Three Black Princesses – Part Three

By Myself

“Next,” I say, “is actually the interesting part of the story: the three black princesses. I love all the furniture draped in black and the princesses themselves dressed in black. That suggests to us that there is some state of mourning going on, but we see no corpse.”

I puff on my pipe before speaking again. “The white spot on their faces, what can that stigmata signify?”

Myself ponders. “Black is the color of evil, but I don’t think white represents only good in our story’s images. I believe white is what widows wear in India among the Hindus and not black as in the West, and does this story have its actual origins in India, as the story itself suggests? What of the wax of the consecrated candle dripping on them and turning them half white?”

“We are getting ahead of our story,” I say. “At this point, he agrees to help them break a spell by not speaking to them or looking at them for a year. That is a pretty namby-pamby challenge. No herculean, impossible task, no suffering on his part. And yet, he can’t achieve it.”

“Again, we get ahead of our story,” myself reprimands.

I smile to myself. “Ok, back on track. The youth wishes to visit his family. Here we enter into the Beauty-and-the-Beast/Psyche-and-Cupid motif with a bit of gender reversal.”

“You know,” myself relights his pipe, “the clothing thing is inserted at this point, which reminds me of a Nassardim story.”

“Yes,” I say in delight, and we tell each other the tale in tandem.

“Nassardim, invited to a feast, shows up poorly dressed.”

“He is not allowed entrance and returns home to put on better clothing.”

“Now, with respect, he is accepted into the company.”

“To his host’s distress, Nassardim stuffs food up his sleeves, saying, ‘Eat, eat.’”

“’Nassardim,’ says the host, ‘what are you doing?’”

“’Well,’ says Nassardim, ‘when I appeared poorly dressed, I was sent away. When I reappeared well dressed, I was escorted in. Therefore, this feast is not for me but for my clothing.’”

We laugh at our own joke.

“Seriously though,” I say, “this story’s treatment of the motif in question is unusual.”

“There is,” myself contemplates, “the clumsy handling of the candle wax. First, a consecrated candle occurs in no other story that we know of. This is one of those Christian insertions for which the Grimms were open to, given their bourgeois audience.”

“What bothers us,” I say, “is that his mother instructs him to drop the candle wax on the princesses but with no indication as to why or for what purpose. When he does drip the wax, it is described in the story as an accident. Not to mention he is looking at the princesses in violation of his promise to save them.”

“Clumsy, as we agreed,” concludes myself.

“Let me press our point about how unusual this is,” I say. “Psyche drips the wax on the sleeping Cupid, then has to pursue her flown lover through the rest of the story. In our version of the motif, the dripping of the wax causes the sudden, closing apocalypse.”

“Yes,” says myself, “while he suffers a broken leg, what happened to the princesses’ blood calling out for revenge and their three chained brothers tearing him apart?”

“Not much,” I frown. “If I recall, we searched for a story about three chained brothers at the time we first read this but came up with nothing.”

“Now,” myself says, tapping out our pipe, “that we are at the end of the story, where the wax has turned the princesses half white; does that bring up the notion of yin and yang, especially with the previous white spot on their faces?”

“We both know that is a stretch,” I say. “The symbol of yin and yang does not appear in the Hindu representations. It is more of a Taoist thing, but not unknown to Buddhists, but there are not that many Buddhists in India despite the religion’s origins. However, the notion tempts us.”

“A given,” myself agrees. “Therefore, overall, what do we think of this tale?”

“Despite the pyramid’s efforts,” I say, picking the crystal up again and looking into its facets, “and regardless of some enticing images, I’ll guess the story’s significance will continue to ellude us.”

I set the pyramid back down on the table. I see that I am alone in my study.

Your thoughts?