Another Picnic

Richmond Park, one of the royal parks, is the destination for our picnic. Oh yes, another picnic! What is summer without numerous picnics?

This one is Melissa’s idea. The park is her choice, the exact location in the park is her favorite, and the menu of her inspiration will be delightful if not as varied as our last picnic’s repast.

Both Thalia and Jini give quiet squeals of wonder when they spot a herd of fallow deer grazing contentedly, even before we reach our intended spot. We will hardly be out of sight of them the entire time, nor of the kestrels flying overhead.

I spread our blanket under an old, old oak tree, and we settle ourselves around it on low beach chairs. I, for one, need a bit of back support on such occasions.

Before opening Melissa’s basket, we look to Thalia for the traditional story. To my surprise, she nods to Jini.

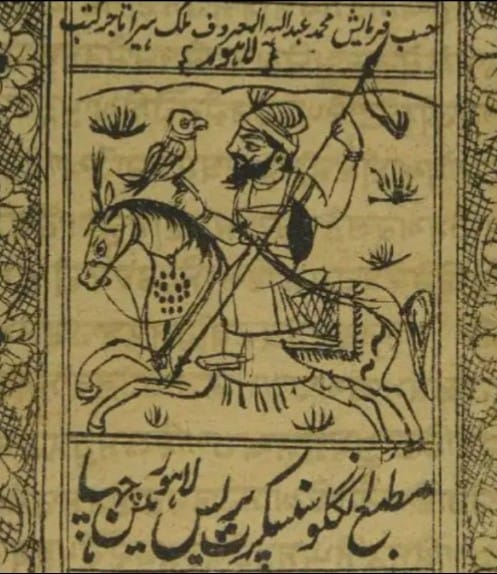

“I have a story for you,” Jini says. “It’s from my people, called Raja Rasalu.”

“Once there lived a great raja, whose name was Salabhan, and he had a queen, by name Lona, who, though she wept and prayed at many shrines, had never a child to gladden her eyes.”

To my pleasure, I realize Jini intends to recite, not read, her tale to us.

Eventually, before a child is granted to the queen, a fakir tells her that her son, whose name will be Rasalu, must not see the light of day for twelve years. If she and the king look upon his face for all that time, or all three will die.

The lad grows up constantly attended to, well educated, and in the company of a colt, born on the same day as he, and a parrot, both his constant companions. At eleven years of age and impatient, he goes out into the world before his time. His parents refuse to “see” him, and he leaves without meeting them face-to-face, never to be in their presence again.

Rasalu, fully armed, astride his faithful horse, ventures forth determined to play games of chaupur with Raja Sarkap, in which the stakes are always high. During his travels, he takes shelter in a graveyard during a lightning storm and has a long conversation with a headless corpse. The corpse turns out to be the brother of Raja Sarkap, through whose hand he lost his head. He warns Rasalu and advises him to make a pair of dice out of a bone from the graveyard to match against Sarkap’s enchanted dice.

Traveling on, Rasalu saves a cricket from a fire, and the cricket gives Rasalu one of his feelers, promising him aid if he burns the feeler to evoke the cricket. Bemused, Rasalu accepts the gift.

Coming to Sarkap’s kingdom, he is greeted by the raja’s seventy daughters, the youngest of whom falls in love with him. The other sixty-nine want him to pass a test. They mix millet seed with sand and order him to separate them out. Rasalu calls upon the cricket, and the cricket’s swarm easily performs the task.

The seventy daughters then want him to push them on their swings. He puts them all in one swing and gives it such a push, they land on their heads. The youngest, now disenchanted, goes to her father to complain. Sarkap understands who Rasalu is and challenges him to games of chaupur.

Before the games, Rasalu—always compassionate toward the needy—saves the kittens of a mother cat, who gives him one of her litter to put in his pocket. During the rounds of chaupur, Rasalu loses his armour, his horse, and is about to lose his head, when his faithful horse reminds him of the bone dice.

During the game, Sarkap’s rat, Dhol, had been running about, knocking over the pieces to distract Rasalu, but now Rasalu insists upon using his dice and brings out the kitten to keep Dhol at bay. After that, Rasalu is victorious and claims Sarkap’s head.

At this point, Sarkap is informed that one of his wives has had a daughter. Rasalu trades Sarkap’s life for the daughter. The daughter is shut into an underground palace for twelve years, and a mango tree is planted at its entrance. Rasalu declares that he will marry the girl when the mango tree blooms.

Jini bows to indicate the end of her story.

We applaud.

Fairy Tale of the Month: August 2023 Raja Rasalu – Part Two

Plot Thickens

Melissa opens up the wicker basket, setting out the quinoa-kale salad. “If that is a story of your people, I will assume your family is from the Punjab?”

Jini smiles. “You are right.”

“Raja Rasalu is something of Northern India’s Siegfried. There are a number of legends about Rasalu, poetic sagas, if I recall.” She looks at me, knowing how little I know about the subject.

“Yes,” says Jini. “My parents brought me up to be English, pushing our own culture aside. I am only now beginning to teach myself about my origins, and, like Thalia, love the fairy tales and legends. I see so much in them.”

“Good,” says Melissa, setting out scotch eggs (I snatch one immediately). “But like the Arthurian tales, for which there are multiple sources that don’t agree with each other, you will find the same disagreements in the Rasalu tales.”

“Such as?” Jini’s eyes glimmer as she stretches out her hand for a Jaffa Cake.

“Well, there is Rasalu’s older brother, Puran. According to some legends, it was Puran who, at his birth, was sequestered for twelve years and could not have his parents look upon him.”

As Melissa slices some bara brith, she continues. “In another version, Salabhan’s second and younger wife makes false accusations against Puran, the son of Salabhan’s first wife, after Puran rejects the younger wife’s advances. In fury, Salabhan has Puran’s hands and feet cut off, and his body thrown down a well.

“Puran survives for twelve years at the bottom of the well, being fed by birds and animals, until a fakir discovers him, retrieves Puran from the well, and, through his powers, restores the severed limbs. Puran studies under the fakir and becomes one himself.

“As a fakir, he returns, unrecognized, to his father and stepmother and grants the queen the long-sought-for child, but with the stipulations of the twelve-year isolation and no visitation. Something of a reflection of his own travail.”

“Wow,” says Thalia. “In Jini’s version, it is some fakir who sets up the terms, and here it is Rasalu’s saintly half-brother. That’s some heavy editing going on!”

I nibble on some Jacob’s Cream Crackers topped with Cornish Yarg. “I am afraid this has often happened when foreign tales get taken over by a different cultural viewpoint. They get disassembled and reassembled, kind of like a Picasso painting.”

“All tales, including these, may get bowdlerized as well,” Melissa adds.

“By the way,” I ask, pouring myself some blueberry-and-mint iced tea (I am glad she had the sense not to bring wine with two young girls in tow) “What is the game of chaupur?”

“Oh, very old,” Jini says. “The board is made of cloth in the form of a cross full of very colorful squares. Each arm of the cross has three columns of eight rows. Each player has four pawns. There can be two players or two teams of two players each for each arm of the cross. The pawns move depending on the value of the seven dice thrown.

“What I don’t get is the dice I always see are made of cowry shells, not bones. Anyway, it’s popular with old people. I don’t have the patience for its impossible rules. The game can go on forever. The game ends when someone gets all four of their pawns to the center.”

“Hmmm,” I say. “I’m old. I may have to try it.”

Jini blushes.

Fairy Tale of the Month: August 2023 Raja Rasalu- Part Three

Number Twelve

“I have to wonder about the number twelve,” I say, turning my attention to some crisps. “Here in the West, there are the twelve days of Christmas, the twelve months of the year, and the twelve-hour clock, all dealing with time.”

“Ah, but,” says Melissa, “I never heard of twelve years of isolation or confinement. In the Grimm canon, Maid Maleen is shut in a tower for seven years. The six swans’ sister has to not speak or laugh and sew six shirts out of aster flowers for six years. A twelve-year sentence of this nature, I don’t recall.”

Our conversation falls off for a while as we enjoy Melissa’s picnic offerings.

“That cricket,” Thalia says, finishing off a scotch egg, “sounded familiar. He was an animal helper, but there was only one, not the usual three.”

“What about the kitten?” Jini asks.

“Not the same thing. Animal helpers give the hero some way of calling them when in need. The kitten simply ended up in his pocket for his use.”

“You make a good point,” Melissa muses. “We may be seeing the origin of a motif. Let me suggest that this notion of an animal helper giving the hero a token or evocative chant to use when in distress, in exchange for a service rendered, came down the Silk Road to Europe.

“Our tellers, knowing a good thing when they heard it, tripled the effect, creating the motif of the three animal helpers. The West is warm to the pattern of threes.”

“I like the notion,” I say, “but who influenced whom?”

“Oh, they influenced us. Rasalu legends date from the second century AD. The fairy tales, as we know them, with their body of motifs, were developed around the twelfth century.”

“Oh,” says Thalia, “there’s the number twelve again.” Both she and Jini giggle.

Melissa smiles. “I am sure it is coincidental.”

“And then,” I say, goading, knowing there are teenage girls in company, “we have a talking horse that gives Rasalu good advice.”

“Yeah!” they chorus.

Melissa rolls her eyes. “If there is a horse in the tale, it is bound to say something. Any animal in fairy tales can talk, but I feel horses are particularly chatty.”

“I did notice,” says Jini, “there isn’t an animal in my tale that Rasalu cannot talk to.”

“And no one is ever surprised by it,” Thalia puts in. “Where in any fairy tale are the words, ‘Oh! You can talk.’ Doesn’t happen.”

“Another good point,” says Melissa. “There are certain assumptions that the fairy-tale genre always makes.” She ticks them off on her fingertips.

“Animals can talk.

“Royalty has magical powers.

“Witches appear poor, even if they have hoarded wealth.

“Rather few heroes and heroines have a name—well, that only applies to the European tales.

“There will likely be a marriage in the story.

“If there are siblings, there will be two, three, six, or seven. Never four or five. Well, okay, in Jini’s tale, there are seventy sisters.

“There are very few fairies in fairy tales. We should be calling them ‘wonder tales.’

“If I thought more about it, I could come up with other notions.”

“Does that mean fairy tales, or should I say ‘wonder tales,’ are rather predictable?” I argue.

“Not at all. But if so, as most popular literature does, even if predictable, it aims to satisfy.”

I am satisfied with that answer.

Your thoughts?