Wolf at the door.

I keep getting emails from the Natural Resources Defense Council asking me to throw money to the wolves. I get these emails because of the art (almost science) of those who specialize in targeting susceptible audiences who wish to entertain the idea of parting with their money for worthy causes. These entrepreneurs are heir to the thoughts of that great promoter of performing artists, P.T. Barnum, to whom is attributed the phrase, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

In present-day American society we are ambivalent toward wolves. They are both a threat to livestock and on the endangered species list. City dwellers feel soft hearted toward these creatures, seeing them as distant echoes of an America passing, already lost to the urban landscape. Those living close to the wolves’ natural habitat may well feel differently about them.

When it comes to the fairy-tale treatment of wolves, as in “The Wolf and the Seven Kids,” I am not sure we are talking about wolves at all. I think we are talking about the embodiment of evil.

I am not talking about fairy tale’s anthropomorphizing of animals. We dress animals up in hats and coats. We have them build and live in houses. All very enchanting and entertaining, but not what I am talking about.

I’m talking about the nature of fairy tale wolves. Actual wolves are scary animals. If you or I were to meet a pack of wolves, while we are alone, in a forest, at night, they would not consider our donations to the NRDC. However, notice the plural. There are no packs of wolves in fairy tales.

The fairy-tale wolf is much more synonymous with the devil than he is with his fellow creatures in the wild. As listeners, we are never allowed to feel sympathy for the wolf (setting aside some clever modern-day spoofs to the contrary). Ultimately the wolf is punished for his deeds. In the case of “The Wolf and the Seven Kids,” the mother goat cuts open the wolf’s stomach as he sleeps, releasing her children and replacing them with stones. When the wolf goes to the well to drink he topples in and drowns. The seven kids and their mother dance around the well in joy. This is the proper course of punishment in fairy tales.

In grander tales such as “The Lord of the Rings” and “Star Wars” the embodiment of evil is represented by Sauron and Emperor Palpatine. Like the wolf, they represent all that is unwholesome. Unlike the wolf, they are supported by a host of minions, some as powerful as Saruman and Darth Vader. When the hero or heroes destroy these representations of evil the minions disperse, and wholesomeness is restored. While the fairy-tale wolf does not have his minions, I am suggesting they too would disperse if he did.

I am left to wonder, if the fairy-tale wolf has lost his status as an individual member of a pack, to be put forth as the sole embodiment of evil, do not these tales misrepresent evil?

When Americans’ symbols of evil, Saddam Hussein and Osama Bin Laden, were destroyed, what happened to their minions? Did a period of peace and contentment follow?

Do fairy tales offer up a false hope? Do they mislead us in the nature of evil by putting evil into one solitary body? Or, are fairy tales responding, as best they can, to our inability to comprehend evil as complicated and diverse?

Fairy Tale of the Month: August 2011 Seven Kids – Part Two

About those Animals

I settled down in my study to write this blog not knowing what I wanted to write about. Our cat passed through the room wearing a vest and breeches, breeches. He produced a pocket watch, checked the time, then with a snap of its lid, hurried out, slamming the door behind him. I wish he wouldn’t do that. Slam the door I mean.

We love giving our pets human attributes. How necessary are those dog sweaters, really? How many times have we photographed dogs wearing glasses? How many dogs know how to shake hands?

Cats will not put up with much of these activities. We have a photo of one of our cats in a baby carriage, dressed in doll clothes. As a result, the cat shunned our daughter ever after.

The delight we take in these doubtful costumed antics gets transferred to, and expanded in, fairy tales. Looking at “The Wolf and the Seven Kids,” Old Mother Goat lives in a house furnished with table, bed, oven, cupboard, washbasin, and clock case (largely ineffectual hiding places for her kids). The wolf converses with a shopkeeper, a baker, and a miller (whom the wolf threatens). During the course of action Old Mother Goat cuts open the sleeping wolf’s stomach, then deftly sews him back up again, seemingly without benefit of opposable thumbs.

In another set of fairy tales we don’t dress up our animal characters and we return them to their habitats, but give them magical powers. My favorite among these is Falada, the talking horse in “The Goose Girl”. Another example is the Flounder in “The Flounder and the Fisherman.” A good half of these magical helpers turn out to be humans under enchantment.

Do we do this to our animal friends for sheer entertainment, or are there other, deeper reasons?

There is a different feel about our anthropomorphizing when we get to the half-humans—mermaids, Centaurs, pans—who populate a mythical world. Stories about them embody a haunting uneasiness. Particularly the mermaid in folklore has a seductress nature. Marriages between them and humans are usually ill fated, as are the unions between selkies and men. Selkies are a somewhat different category, being seals in the water and humans on land, not being half-human on the upper half and animal on the lower half, but rather shedding their animal skins. In all cases, these relationships left us with a sense of the uncanny.

If we reverse the order of upper half human and lower half animal we are plunged back further in time to the Egyptian pantheon, that house the likes of Horus, Sobek, and Sekhmet, who bear the heads of a falcon, a crocodile, and a lioness respectively. These are gods and goddesses, idols of worship, more than the playthings of our idle imaginations. It is they who act out the Egyptian cosmology in time to the rise and fall of the Nile. Can we draw a line between Anubis, the jackel-headed god of the underworld and the big bad wolf?

I sense an undercurrent of suspicion that we fear we are not as high above our animal companions in the hierarchy of existence as would please us.

Our cat came back into the study mumbling under his breath, grabbed my copy of Grimm, and left again. I wish he wouldn’t do that. Mumble I mean. I don’t know what he said.

Fairy Tale of the Month: August 2011 Seven Kids – Part Three

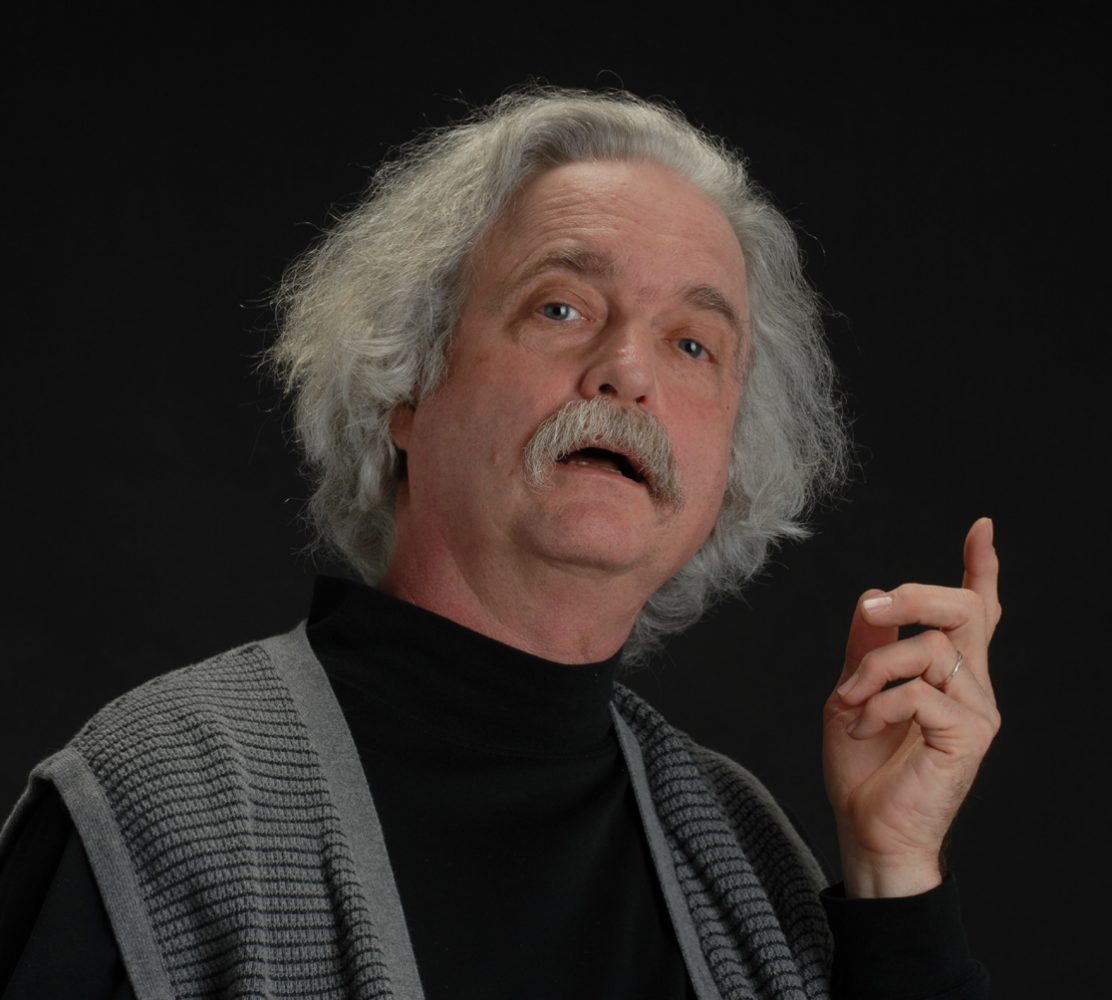

Otto Ubbelohde

Otto Ubbelohde

An upset stomach

“The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach.”

“I have butterflies in my stomach,”

“I can’t stomach that.”

The stomach comes in for its fair share of inclusions in adages and expressions. Holidays mean special foods for our stomachs, from turkey and hot dogs to cookies and candy. Entire industries are dedicated to the condition and shape of our stomachs. For as much concern as we have with our stomachs, it plays but a small, although specific, role in fairy tales.

Only two tummy-mofits (Am I coining a term?) come to mind and one of them isn’t strictly a stomach. I will first deal with (to get it out of the way) the gizzard.

With due respect, it is a magical gizzard. The two best loved gizzards belong to Drakestail of the story “Drakestail” and the little red Hungarian rooster of “The Turkish Sultan.” Both gizzards have the ability to hold objects far beyond expectations. Drakestail’s contains a fox, a ladder, a river, and a wasp nest. The Little Rooster holds a well of water, a bee’s nest, and, in the end, all of the Sultan’s treasure.

The stomach that interests me most is the wolf’s. (There is a Norwegian troll stomach of some merit, but that is a tale I have not explored.) In “The Wolf and the Seven Kids,” after a third attempt at deception the wolf succeeds in eating six of the seven kids, but with such haste and greed that he swallows them whole. The seventh kid leads Old Mother Goat to where the wolf is sleeping off his meal. Seeing movement in his stomach, she gets scissors, needle, and thread, cuts open the wolf’s stomach, and lets out her kids who gather stones to replace themselves, after which the wolf is sewn up again. Upon waking, in some discomfort, the wolf goes to the well for a drink. As he leans down the stones roll forward tipping him into the well to drown.

I’ll compare the above tale with another tale. This tale is Greek, and I’ll suppose older, but I cannot be certain about the age of any tale and its origins. The parents of the Greek pantheon were the Titan, Cronus, and his sister/wife Rhea. It was prophesized that Cronus would be overthrown by one of his children, just as he had overthrown his father. Cronus attempted to get around the prophesy by eating his children. Rhea didn’t like that much, and when she gave birth to Zeus, she substituted a stone statue for the child, which Cronus swallowed instead.

In some versions of this tale Zeus is raised by the goat Amalthea. When Zeus grows up he overthrows Cronus as predicted, by cutting open Cronus’s stomach, thereby releasing his siblings. Oh, by the way, Cronus had seven children. Well, okay, Chiron was a centaur born of the nymph Philyra, and not one of the gods, but, hey, close enough for fairy tales.

I leave you to draw the parallels.

Your thoughts?

Symbols of evil

Perhaps the wolf is the minion -that one demon sent to tempt and torture one individual or a few individuals- like in the three little pigs or little red riding hood. In all three tales the wolf only comes around when the authority figure is absent. Perhaps there is some greater, scarier being sending out the wolves.