Some Fortune

We are gathering in the study for our Christmas Eve reading by Thalia. By gathering I mean, of course, the fairy, Johannes, the brownies, and myself. My cell is on speaker so that Melissa may listen in.

Thalia waits while I tend to the logs in the fireplace, the fairy perches on her shoulder, Johannes curls up on the window seat, the brownies settle into a dark corner, and Melissa is virtually propped up by some books on the study table. I settle into my comfy chair, noticing the book in Thalia’s hand, Folk and Fairy Tales of Denmark, Vol. 2. Thalia really has begun to explore the fairy-tale canon beyond Grimm.

“Tonight,” she says, “I will read to you Hans’ Fortune.”

I am a bit surprised. I know the tale and I don’t see anything Christmas-like about it.

Hans, a young man thought by others as simple, overhears a conversation about seizing one’s fortune with both hands. He contemplates this and soon declares to his parents that he will go off to seek his fortune.

He wanders aimlessly until one day a coach, carrying the local squire, passes by him and Hans lunges with both hands outstretched but fails to grasp anything, landing upon the ground scratched and bruised.

Curious, the squire tells his driver to turn around. Hans explains that he perceived the squire, coach, driver, and horses as the type of fortune he sought and tried to seize his fortune with both hands. In turn, somewhat inexplicably, the squire invites Hans into his employment. Besides tending to the squire’s cow herd, Hans was to accompany the squire on his trips to town and market.

During these trips, Hans proves to be talkative, and the squire learns from him many things of which he had not been aware. The squire surmises that Hans, though he appeared simple, was more clever and observant than he let on, was forthright with his opinions, and above all honest; a man to be trusted.

One day, at market, the squire proposes a little contest. He would select six horses to purchase and Hans would select another six and they would see, in the end, who made the better picks. The squire picks six fine-looking horses and Hans picks six underweight, ill-tended horses, but at a third of the price. After six months, the horses Hans had chosen—and due to tender care—are more valuable than the six the squire selected.

And so it went with every decision on the squire’s estate; Hans’ opinion was requested, followed, and turned out for the best. He rose in the squire’s esteem.

When the squire turns his thoughts toward marriage, he has in mind the two daughters of the church warden but doesn’t know which to marry. On one of his courting visits, he takes Hans with him to render an opinion. Hans feels neither would be a suitable wife for the squire, but rather the warden’s kitchen maid would be best. The squire resists the idea at first but could not get Hans’ advice out of his mind.

The squire proposes to the kitchen maid and leaves Hans to invite the guests. Hans invites the king and queen. To the squire’s surprise, the queen makes a great fuss over the bride, giving her a royal wedding gown in which to be married. The queen continues with her attention to the bride during the wedding feast until the king takes her aside. The queen confesses that, because the king had once ruled an unfaithful woman was to be punished by having one of her twin children killed, when the queen gave birth to twin daughters, she had one of them hidden away. That daughter is the kitchen maid.

The king immediately rescinds any implication of his ruling and the truth comes out, right there at the wedding feast. The newly acquired son-in-law and the newly discovered daughter are elevated to the level of duke and duchess and granted a dukedom.

Hans is given the old estate and marries one of the church warden’s daughters.

“Hans,” Thalia concludes, “had found his fortune.”

A muffled applause comes from the shadowy corner. Dimly, I can see the brownies are ecstatic about this story. Thalia smiles at them gently.

I must confess, Thalia knows her audience.

Fairy Tale of the Month: December 2020 Hans’ Fortune – Part Two

About Brownies

I’d not heard the term “video chat” before Melissa suggested it, but I realized what it was when she said it. Over the phone, she talks me through downloading the software—an app, she calls it—and I wait for her to “invite” me.

After a couple of messages and buttons to click there is Melissa on my screen.

“Good Lord,” I say, “where are you? There’s a palm tree and an ocean behind you!”

“I can’t hear you. Turn on your mic.”

“I don’t have a microphone.” I can see myself on the screen as well and how confused I look.

“My dear,” says Melissa, “you are such a Luddite. Click on the icon—the little picture of a microphone with a line through it in the lower-left corner.”

“Oh, there it is. Got it. Where are you?”

“Oh, I wish,” grins Melissa. “It’s just my background. I am not that fortunate to really be there.”

“We both could use a bit of Hans’ luck.”

“Thalia read very well. I believe I heard the brownie react to her.”

“I am sure,” I say, “she read the story with them in mind.”

“There was something brownie-like about Hans.”

“How’s that?”

“He never asks for anything, is always there to do the squire’s bidding, does not promote himself, and carries the aura of prosperity for the household or, in this case, the entire estate.”

“True,” I say, “that may be why my brownies were attracted to Hans and saw themselves in his story. However, I have read that brownies can be tricksters, even turn into boggarts.”

“Only if you offend them,” Melissa frowns. “I assume you treat them well.”

“Ever since I realized my floors and counters were spotlessly clean and it wasn’t me doing it, I have given them a bowl of milk in the kitchen every evening.”

“Wait,” says Melissa, her image stuttering a bit, “shouldn’t the traditional bowl of milk be set by the hearth?”

“I put it by the hot-air duct in the corner of the kitchen. That seems to suffice.”

“A modern adaptation, I guess,” she says. “By the way, why do you have more than one brownie? They are almost always solitary beings, one per household.”

“The exception proves the rule, I will suppose. They appear to me to be a family of four, but I am not sure of the number because they are shy and reclusive. I rarely see them outside of Thalia’s study readings. I have read they can be invisible if they wish.”

“And don’t give them any clothing,” Melissa warns while her image freezes.

“Quite right. Poorly dressed though they are, new clothes are a thing with them and they see it as an offense. Sounds a little like the Grimms’ Elves and the Shoemaker.”

“I think Wilhelm was conflating elves and brownies,” Melissa smiles.

“I am sure of it. I remember hashing this out years ago when Thalia and I first read the Grimm version.”

“But getting back to Hans,” she says, “and his brownie-like behavior; why does he appeal to us in this story?”

“Well,” I speculate, “it ends happily. That is one point in its favor, but let me suggest the tale has a purpose in having Hans (and we can apply this to brownies) serve as a role model of what a servant should be and how a servant (or brownie) should be treated.”

“Ah,” there is agreement in Melissa’s voice, “an object lesson. The squire does treat Hans well and Hans rewards him. In the end, Hans is rewarded for being an exemplary servant. But wait again, isn’t that an unrealistic goal for the serving class to be aspiring toward?”

“Melissa,” I admonish, “you are being coldly analytical, moving toward political correctness. We’re talking about fairy tales. They are all about unreasonable expectations. They are the stuff of our wildest daydreams coming at us from outside ourselves. That is their appeal.”

“Oh, of course,” Melissa smirks. “Forgive my lapse into truth and reality.”

“Forgiven.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: December 2020 Hans’ Fortune – Part Three

Feudal Fortune

Melissa and I take a little break to go find wine for ourselves. When we return, she proposes a toast to the Christmas season. We hold up our glasses to the computer screen. There is not the crystalline-clear clink of glass against glass to greet our salute. I miss that, but I am getting fonder of this video thing as a substitute for life.

“Now,” says Melissa, “about this wandering-off stuff to seek one’s fortune.”

“What about it?” I respond rhetorically. “They did that all the time.”

“Yes, they did that all the time in fairy tales, but did they, in fact?”

“Why shouldn’t they have?”

“Because they were serfs.”

“Oh, you’re right, the peasants anyway.”

“This thought occurred to me one night recently and it didn’t let me go back to sleep.”

“You’re sounding like the agnostic, dyslexic, insomniac who stayed up all night wondering if there really was a Dog.”

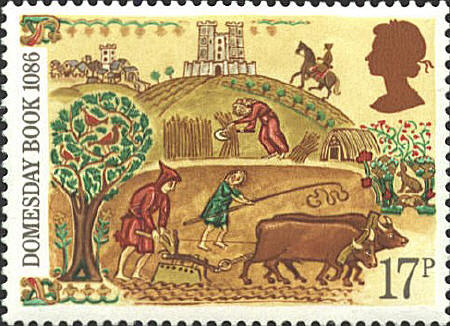

“Behave!” Melissa scolds but tries to hide her smile behind a sip of wine. “Seriously, my impression is that these fairy tales, in the form they have come down to us, developed around the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, pretty much at the height of the feudal system.”

“Remind me about that institution.”

“It really wasn’t an organized system, but rather a similar response throughout the Western world after the fall of the Roman Empire when existing rule decentralized.

“A lord gave land to a vassal in return for his military aid, along with a promise from the lord to protect the vassal. The lords and vassals made up the nobility. The second tier of society was the clergy, some of whom had land granted to them to support abbeys and monasteries. The third tier was the peasants whose obliged labor supported the first two tiers. A small percentage of them were freemen, but most lived in some form of servitude.

“I think townspeople make up another tier, but historians never describe them that way.”

“Perhaps they fall under freemen,” I suggest.

“In any case,” she continues, “most people, particularly the listeners of these tales, were tied to the manor where they lived. If the manor passed into new ownership, the peasants’ obligations passed to the new lord. If a girl wished to marry someone outside of the manor, she had to pay the lord a fee for her release. If a freeman gave up his status and pledged himself to the lord of the manor, he pledged his progeny into servitude as well. Those who tilled the soil for the lord were his chattel. They didn’t pick up and go wandering off to seek their fortunes.”

I drink half my glass while she pontificates. “But didn’t this setup fall apart by the time of the Grimms’ writing?”

“Largely but not entirely. Interestingly, an element in its demise was due to the Black Plague that swept Europe in the fourteenth century, killing a third of the population, leaving the surviving laborers with greater bargaining power.

“Contrarily, serfdom didn’t end in Russia until a decree in 1861, well after the Grimms’ publications.”

I take another sip. “You’ve got me thinking now. We really don’t hear echoes of the feudal system in the tales. I don’t recall the phrase, ‘There once was a poor serf.’ There are plenty of poor people; lots of kings, queens, princes, and princesses; many witches, henwives, and sorcerers; occasionally judges and lawyers, but no one called a serf. The closest word is ‘servant’ but that does not carry with it the connotation of thralldom.

“I think you are right. Sons wandering off, leaving their parents behind to fend for themselves really does not ring true to beings tied to the land by birth.”

“Ha! Gotcha,” Melissa smiles again.

“How so?”

“The answer is that, for young men at least, this motif was their wildest daydreams coming back at them from outside themselves.”

“Ah, escapism,” I say.

“Let’s drink to it. We could use some of that ourselves.”

Melissa’s image freezes again as we raise our glasses. I think I hear the clink this time.

Your thoughts?