Unnatural Child

I am alone this evening—sort of. Thalia and Jini are in the kitchen, along with the fairy, making themselves a late-night snack. I am making myself scarce per Thalia’s instructions. Well, there is nothing I could add to the young girls’ sleepover prattle.

Along with a bit of whiskey, I entertain myself with the trick of running my finger across the spines of books on my shelves, picking one out on impulse, closing my eyes, and opening to a page.

The book I choose is Folk and Fairy Tales from Denmark: Stories Collected by Evald Tang Kristensen, Vol. 1, edited by Stephen Badman. In bold letters is the title, The Prince and the Tiger Child. I settle into my comfy chair and take a sip of whiskey.

There is a husband and wife who have no children and blame each other. The wife goes to the wise woman, who gives her the odd advice to go home, pretend to be ill, and send her husband to her for the cure.

This is done, and the husband is given a small, covered pot, with the instructions not to look inside. He, of course, does and sees three small, cooked fish that he knows as smelts. A bit peckish, he eats one of the smelts. Nine months later, his wife gives birth to a child, and so does he.

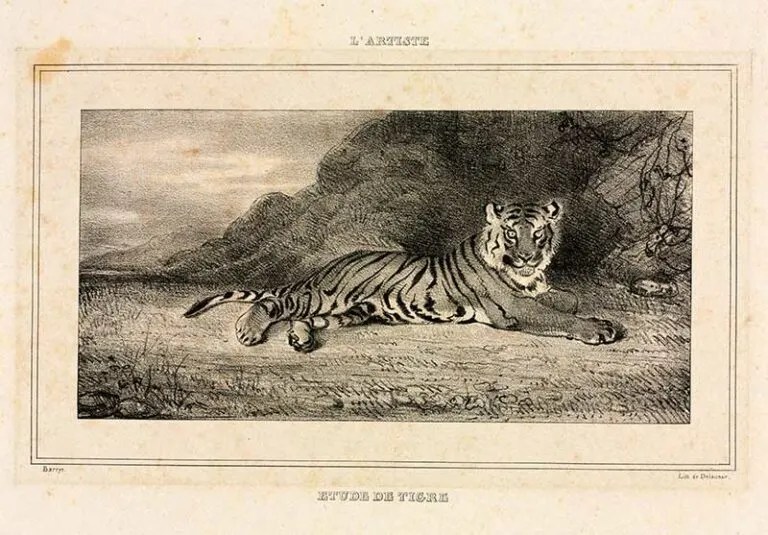

When his wife goes into labor, he hides in the woods and gives birth to a daughter, whom he abandons, mortified at what has happened to him. She is discovered by a wyvern that takes the child into its mouth, but before it can consume the babe it is attacked by a tigress. The tigress, having recently lost her cubs to hunters, takes the child as her own and nurses it.

Years later, the “tiger girl” is discovered by a young king out hunting when his horse paws at the entrance to the girl’s hiding place. The young king marries the girl, much to his mother’s distress. The old queen insists the girl is little more than a wild animal.

When the young king is obliged to go off to war just before his child is born, his mother takes advantage. She steals the child, gives it to her maidservant to be drowned, smears the girl’s mouth with blood, and declares the mother has eaten her own child.

Upon returning from war, the young king refuses to believe what he hears. Two more times his wife bears a child; each time the baby is spirited away, given over to be drowned, and the old queen insists the girl has eaten her children.

However, the maidservant, whose duty it was to drown the infants, did not have the heart to do so. Rather, she put each child in a watertight box and floated the poor being down the river toward its fate. Each time, a different miller and his wife find the floating box and adopt the child as their own.

Meanwhile, the old queen keeps up her campaign, declaring the girl should be burnt. The young king cannot bring himself to that justice. Instead, he sends his queen from the court to tour the kingdom, never to return. She leaves, well provided for, in a carriage drawn by six horses.

As soon as they pass through the gate of the capital city, the young queen finds her voice. Immediately, she instructs her driver to go to the mill where her eldest son now lives. She is well received, and after dinner, as is customary, they play a riddle game. However, the queen demands high stakes if they cannot guess her riddle. She wants another carriage with six horses, a coachman, and their child—her child—as a servant.

The riddle is, “My father is a fish, my mother is a man, a wyvern bore me in its mouth, and I was brought up by a tigress; a horse gave me a husband. I bore my husband three healthy children, all of them died, but all three are still alive.” The miller and his wife, of course, are clueless.

The queen repeats this quest two more times until she has all of her children. When she eventually returns to her husband’s capital city, she enters the castle courtyard with four sets of carriages, one for herself and three for her sons. She is, also, unrecognized by the king or the old queen.

After dinner, the riddle game commences. This time, the young king knows enough about the clues to guess that this is his wife, and all is revealed. The evil old queen is consigned to the punishment she wished upon her daughter-in-law.

“Oh, nice,” I say aloud. “I can confound poor, logical Duckworth with this one when we take our walk tomorrow.”

I empty my whiskey glass.

Fairy Tale of the month: May 2024 The Prince and the Tiger Girl – Part Two

Hill Garden

Duckworth and I wander about Hill Garden and its winding, multilevel pergola at Hampstead Heath, often described as a “secret garden.” Built by Lord Leverhulme as a place to entertain guests in good weather, it had fallen into near ruins but then restored by the City of London Corporation. It makes for a marvelous ramble up and down stairs and through the gardens on a spring day. Especially with the wisteria hanging from the pergola rafters.

I have just finished relating The Prince and the Tiger Girl to Duckworth, and I try not to smile at his bemused expression.

“Let me get this straight,” he gestures with a finger in the air. “A tiger in Denmark?”

“It was there to attack the wyvern,” I say. “Or in other words, they both were exotic beasts to this story’s listeners, on a par with dragons and unicorns.”

“Okay,” says Duckworth. “I’ll let you get away with that one and move on to a more serious story offense.”

“And what might that be?”

“Things like a prince out hunting finding a beautiful woman hiding in some wood; having an evil queen abducting children and rubbing blood on the heroine’s mouth—as improbable as these things are—I understand that these are familiar tropes in the fairy-tale canon.

“However, having the heroine pass through the gate of the city and suddenly be able to talk and know where her children are—knowledge she can’t possibly possess—goes too far beyond logic.”

“Duckworth! I’m ashamed of you,” I declare, suppressing my mirth and pretending to be annoyed. “How often have I told you that one cannot apply logic to fairy tales?”

“Well,” he grumbles, “if not logic, what reason can you apply to explain her sudden insights?”

We come to a bench under one of the pergola and breathe in the scent of the wisteria.

Presently I say, “That she was passing through a gateway is significant. She was leaving her old world into another. Her purpose in the new world was to find her way back to her old world with all the injustices foisted upon her corrected. That is to say, to reclaim her children.”

“Good,” says Duckworth, “as far as it goes, but what about her unaccountable knowledge? Where does she get that from?”

I put my hands to my chest dramatically. “Why, from us, the listener/reader. In the theatre, I think it is called the fourth wall. This is the breaking of the fourth wall, if only for a moment, and the heroine now knows what we know.”

“Oh, poppycock!”

“No, listen. How do we know, you and I, sitting here, on this bench, smelling the wisteria, are not, in fact, the imagination of some writer scribbling us down? What thoughts could that writer put into our brains?”

“Double poppycock!”

I see I will not convince him and take my argument no further. With no signal between us, we rise and continue our amble.

“Here is another thing that bothers me,” Duckworth picks up the conversation. “Not just in this tale but in others as well, the characters inexplicably do not recognize each other, even if, as in this case, they are husband and wife. I recognize long-ago friends from public school, for heaven’s sakes.”

“Ah, here I can give you a possible, logical—which you so adore—explanation. She wore a veil.”

Duckworth cocks his head to indicate I should continue.

“In medieval times and beyond, women of worth wore veils in public to indicate their modesty and high station. Our young queen would certainly have worn a veil and had reason to hide her identity until she had proven herself.”

Duckworth knits his brow. “I thought that was an Islamic thing.”

“No, no. Muslims are newcomers to the religious world. They took the veil from Jewish and Christian traditions of the time. Young girls, serving maids, and prostitutes did not wear the veil. Prostitutes, in particular, could be severely punished for the effrontery of wearing it.”

“Well,” says Duckworth, “you won two out of three arguments, but really, we being figments of someone’s imagination takes the cake.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: May 2024 The Prince and the Tiger Girl – Part Three

A Metaphor

“It is clearly metaphorical,” Melissa says with her usual certainty, taking a sip of tea.

“Metaphorical of . . .” I ask.

“Of women’s journey.”

We sit in the reading area of Melissa’s bookstore, each with a cup in our hands and the teapot in its cozy on the table in front of us, along with a copy of Folk and Fairy Tales of Denmark from which I have just finished reading aloud. Two customers wander through the store. From where we sit, Melissa can keep an eye on the register.

“Really?” I say. “I wasn’t seeing that and am not sure that I do, at least not in terms of metaphor. Her birth, for example, I thought of as something of a joke that worked into her riddle later on. How is that metaphorical?”

“At the time this story was collected—and in some cases still today—a male child was more valued than a female child. The male child was the one to carry on the family name. The male child would receive a higher education or be apprenticed out to learn a trade. For a man to ‘have’ a daughter could be a disappointment.”

“And her abandonment?” I ask. “Little girls aren’t usually left in the woods.”

“Well,” Melissa says, becoming a little unfocused. “In a way, they can be. Again, a girl’s brother may be given the greater share of a family’s resources and attention, and she rather left behind. The tigers and wyverns? These are the good and bad influences that come in and out of a girl’s unstructured career pretty much at random, as opposed to the careful grooming of a brother’s path to success.”

I sense this story is hitting close to home—not my intention—and I alter the trajectory.

“Then enters the prince to change everything?” I suggest.

“Change everything, “Melissa echoes. “Not really.”

So much for a new trajectory.

“He is simply another male figure,” she continues. “However, there is a change. Instead of abandoning the girl, he takes control of her through marriage.”

I know Melissa is divorced. I am going to pour myself a cup of tea and pretend I don’t notice the parallel.

Melissa takes another sip of her tea, then says, “In the context of this story, the prince tries to take control, with all benevolent intentions, but is unable or skillful enough to do so. Another actor, with their own agenda, thwarts his efforts. His own mother.

“I will sympathize. Had it been an advisor, stranger, or friend, he should have been—and rightly so—skeptical of their opinions. But his own mother? That is a special bond hard to break. Yet, he resists.

“In the end, after a campaign of lies and deceit and the claim that the young queen should be burnt, he sends her away from court. The ‘he’ abandons her all over again.”

Ouch.

I will try to divert. “What of the passing through the gateway? What of her suddenly knowing the unknown?” I take Duckworth’s position at this point.

“Yes, that is the transformation. We have often talked about transformations in fairy tales. Endlessly, actually, and here is another.

“When she passes through the gateway, she is liberated from her past. She comes into her own. When that happened to me, I understood things I had not been told. I simply knew as she did.

“Our heroine goes forth and reclaims her life. She takes back, through riddles, her children, all males. I wish there had been a daughter, but that’s just me.

“Myself? I made other choices. I had no children. I abandon the men in my life as they have abandoned me. You, my friend, are a bit of an exception.”

One of her customers comes to the counter, and Melissa rises to attend, ending our conversation.

Thank goodness.

Your thoughts?

Great tale, synopsis and comments, Charles. Thank you for taking it up.

Stephen

Glad you approved.