A View

Melissa and I sit on the 40th floor of 110 Bishopsgate in the Duck and Waffle restaurant, gazing at the stunning cityscape with lights that rise into the sky, blocking out the stars.

We have just driven back from Hertford, where her sister lives and was in crisis—something to do with her husband. Melissa had called me early in the morning, shut down her store, and I drove her north. I spent the day trying not to be there and fled to the house’s veranda. Although I could hear the family members’ voices rise and fall as they came and went, I could not, and did not want to, hear their words.

Long after dusk, Melissa came out on the veranda, looking pale and weary. “We can go now.”

We were halfway back to London before she blurted out, “Her husband is such a brainless fool. Men! I know about stupid men; I married one.”

She fumed a while in silence before saying, “Oh, sorry. Present company excepted.”

“I’m not your man,” I said. “I’m your friend.”

She touched my shoulder, then tapped her phone, and said, “Duck and Waffle,” then to me, “My treat.”

“What? It’s late. Are they open?

“24/7.”

My stomach growled, which reminded me I hadn’t eaten all day.

#

I order their signature Duck and Waffle.

“I’ll do the ‘Wanna Be’ Duck and Waffle,” says Melissa. “Actually, it’s mushroom. Oh, and two glasses of something, after today.”

“I see Waffle on the Rocks on the drink list,” I suggest.

“Sounds perfect.”

The drinks come before our meal.

She is well into her’s when she states, “Pottle of Brains is running through my head like a tune. I guess that’s no surprise.”

I squint. “I’ve heard that one. Remind me.”

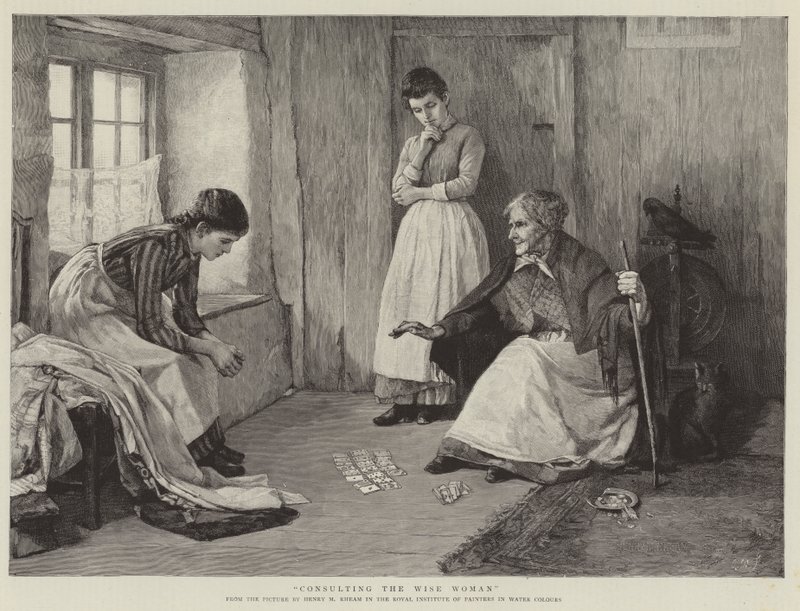

There was once a fool, who, because he was smart enough to know himself a fool, decided he needed a pottle of brains. His old mother encouraged him to visit the wise woman. His mother feared that she would die, leaving no one to take care of her less-than-clever son. She did instruct him to mind his manners.

After a clumsy attempt at minding his manners, he abruptly asked the wise woman for a pottle of brains. She agreed to help, but with conditions. The fool was to bring her the heart of the thing he liked best and then answer a riddle. If he answered the riddle correctly, then he would have his pottle of brains. If he did not answer correctly, then that was not the thing he liked best.

The fool went home and decided he liked bacon the best. With his mother’s consent, he killed the pig and took its heart to the wise woman but could not answer the riddle.

Returning home, he found his mother had died. After much grieving, he realized he liked his mother the best. He couldn’t bring himself to cut out his mother’s heart, so he put her in a sack, which he plopped on the wise woman’s door sill. Again, he could not answer the riddle.

Not even getting all the way home, he sat down by the roadside and cried, where a local lass came across him. She talked him into marrying her, not minding the task of taking care of a fool. She did her task so well, the fool decided that he liked her the best.

A discussion followed as to whether he should take her heart like he did the pig or take her whole self as he did his mother. The wife insisted on the latter, telling him she could help with the riddle.

He despaired, saying women were not smart enough for riddles. He posed the first riddle.

“What runs without legs?”

“Water.”

“What’s yellow and shiny but isn’t gold?

“The sun.”

Hope revived, he rushed her off to the wise woman.

“What first has no legs, then two legs, and ends with four?”

The fool’s wife whispered in his ear, “Tadpoles.”

“Then you have your brains already,” the wise woman replied.

“Where?” he asked, searching his pockets.

“Right there in your wife’s head.”

I chuckle as our meals arrive.

Part Two

About Stereotypes

I find myself distracted by the undulating, yellow ceiling tiles in this section of the restaurant. Still, I catch myself and keep my attention on the excellent duck, the brilliant cityscape below, and Melissa’s tale.

“I can imagine why you are drawn to this tale,” I say as I dribble the mustard-maple sauce on the waffles. “It makes fun of the fool—a male—who, despite thinking he likes his mother and his wife the best and being aided by a wise woman, who is posing the riddles, thought they were not smart enough to solve them. The story proves otherwise.”

“He had the excuse of being truly a fool,” Melissa allows. “But he did not come to that conclusion himself. He absorbed it from the society around him.”

I point my fork at her in agreement before I dig it into the fried duck egg sitting on top of the duck thigh. “The portrait of women in the fairy tales is,” I say after a pause, “uneven.”

Melissa smiled. “I suspect it depended in part on the gender of the storyteller when the story was collected, but a greater effect was the social attitude of the culture in which the story traveled.

“For example, in the Grimms’ King Thrushbeard, the headstrong princess loses her status and does not regain it until she is humbled. The Grimms were German to the core.

“However, in the Irish version of that tale, Queen of the Tinkers, the princess does not regain her status by sticking to her convictions.”

As Melissa picks up her fork, I set down mine. “I am going to push back a little on the tales being only unfair in their depiction of women. I’ll suggest they are equally unfair to men.”

“Go on, I’m here,” she says, contentedly nibbling on her mushroom.

“The fairy tales operate on stereotypes. There is no room for complex characters. They are boiled down to their essentials.

“I’ll start with the loving mother who usually dies to be replaced by the evil stepmother or evil queen, followed closely by evil stepsisters. If there are real sisters, they will give bad advice.

“Then there is the princess who falls from grace and must find her way back, or is resistant to getting married, or, as in your example, she is both.

“I’ll not forget the clever peasant girl who comes out on top. There are seldom brothers and sisters, unless the tale is about a brother and a sister. I think I can end the list with wise women and witches.

“I doubt there are many females in the tales who do not fall into one of these categories.

“As for males, first are fathers. They can be tradesmen, farmers, millers, fishermen, tailors, woodcutters, and even kings. Chances are good they will do something reprehensible, like getting remarried or picking a rose from a beast’s garden, before disappearing, story-wise.

“Kings can be a little more durable. They are never evil, but they are inattentive, demanding, obtuse, plotting, and occasionally wise.

“Then there are the brothers. They come in combinations. If there are two brothers, there are two flavors: a rich brother and a poor brother, or one brother must save the other. If there are three brothers, then the youngest is a simpleton but honest and pure, while the elder brothers are too clever and/or evil for their own good.

“The solo, young adventurer, often a prince, is, of course, noble, destined to save the princess.

“There are not nearly as many wizards as witches. I can’t think of other male roles.”

“This mushroom is so good.”

I glance at Melissa. “Have you been listening to me?”

“Ah, sort of. Maybe. But I’m sure you’re wrong.”

Part Three

A Fool

“Are fools always wrong?” I can’t help baiting her.

She glances at me curiously for a second, then relents. “Oh, you are not a fool. Not always. But true fools, yes. Even if they chance to be right, they come to that from the wrong direction.

“Pottle of Brains I found in Joseph Jacobs’ More English Fairy Tales. In that same volume, he included an almost identical tale with a different ending, called Coat O’ Clay. In that tale, the wise woman tells the fool he will remain so all his days until he gets a coat o’ clay, and then he will know more than she.

“Well, he rolls himself in muck and mire in pursuit of a coat o’ clay. He has various encounters, including the possibility of a wife, but it all turns out badly. What the wise woman meant was that it would not be until he was buried in his grave would he no longer be a fool but know death.

“Oh, that’s a little morbid,” I can’t help saying. I am sure she is thinking about her brother-in-law, so I’ll try to shift the topic just a little.

“What about the simpletons of other stories? Do they come in for the same treatment?’

“No, no!” Melissa raises her glass to toast them. “They are of a different order. They are not fools. If they are simple, they simply make good, honest, and moral choices. Such as in the Grimms’ Queen Bee. It serves them well.”

“What prevents the simpleton from making foolish choices? Why always the good, honest, and moral choice? There must be some mechanism that the fool lacks.”

This gives Melissa some pause. I wait, relishing the last of the duck thigh.

She scowls a little at me. “I am going to object to the word ‘mechanism.’ The simpleton’s choices are not triggered by something. The simpleton is guided by an inner light that recognizes what is just.

“I think I know what speaks to the listener in the simpleton tales.” Melissa twirls the stem of her glass before continuing. “The listener instinctively relates to them. Do we all want to see ourselves as being like them? Good, honest, moral simpletons? Could it be that simple?”

She finishes her drink and calls the waiter for another. “I am going to change my mind.” Melissa stares at the weird yellow ceiling tiles. “There is a mechanism. It’s compassion. Going back to Simpleton in The Queen Bee—his name is Simpleton in one of the versions—he takes pity on and defends the ants, ducks, and bees, whom his two elder brothers would have harmed. The creatures become his ‘helpful animals,’ which is the reward for his compassion that propels him, eventually, to kingship. The simpletons have compassion. Fools do not.

“My brother-in-law is a fool, but am I also a fool? I have no compassion for him. What does that make me?”

I tried to divert her, but without success, I see. I will simply make sure she gets home safely tonight.

Your thoughts?

I love the image this generates “Pottle of Brains” – Thanks ever so much for your work.

I am glad you enjoyed. I am not sure what a “pottle” is, but we automatically understand.