Cold Day

It being a cold January afternoon, I bundle up wearing my warmest socks, long johns, heaviest coat, and fluffiest scarf. I stand at the French doors of my study looking out over the lawn, flecked with flakes of snow, toward the Magic Forest.

Wait, why am I going out? This isn’t my idea. It’s cold.

I am about to take my coat off when it hits me.

Ultima is calling me.

I put on my gloves, put my head down, and forge my way outside into the weather.

Entering the forest, the temperature softens considerably. I have noticed before that the weather is usually nicer here. As I expected, Ultima waits for me by the edge of the pond. I take a sitting stone beside her.

“Oh, so good to see you again,” she gushes, handing me a book. It is Fairy Tales from the Far North, by P.C. Asbjornsen—from my library.

So,” I say, “that’s where it went.”

“As always,” she continues, “the customs of your world confuse me. What is this ‘marriage’ thing all about?”

“For example?” I ask.

She takes back the book and returns it to me with her finger on the title page of the story The Squire’s Bride.

There was an old, widowed squire who wished to remarry and chose a pretty, young lass of a poor family, thinking she would be eager to marry him. That proved not to be the case, and the more she refused his advances, the more determined he became.

Going to her father, he struck a deal, but the father fared no better at convincing his daughter to marry the squire. The squire grew impatient and demanded the daughter from her father, and they conspired to entrap the girl. The squire would prepared for an elaborate wedding and then, under false pretenses, would call for the maid.

When all was set, the squire, in his usual brusque manner, sent a lad as messenger—without much explanation and to make haste—with the instructions to tell the father to deliver what he promised. The maid saw through the ruse and gave the lad a bay mare to be delivered.

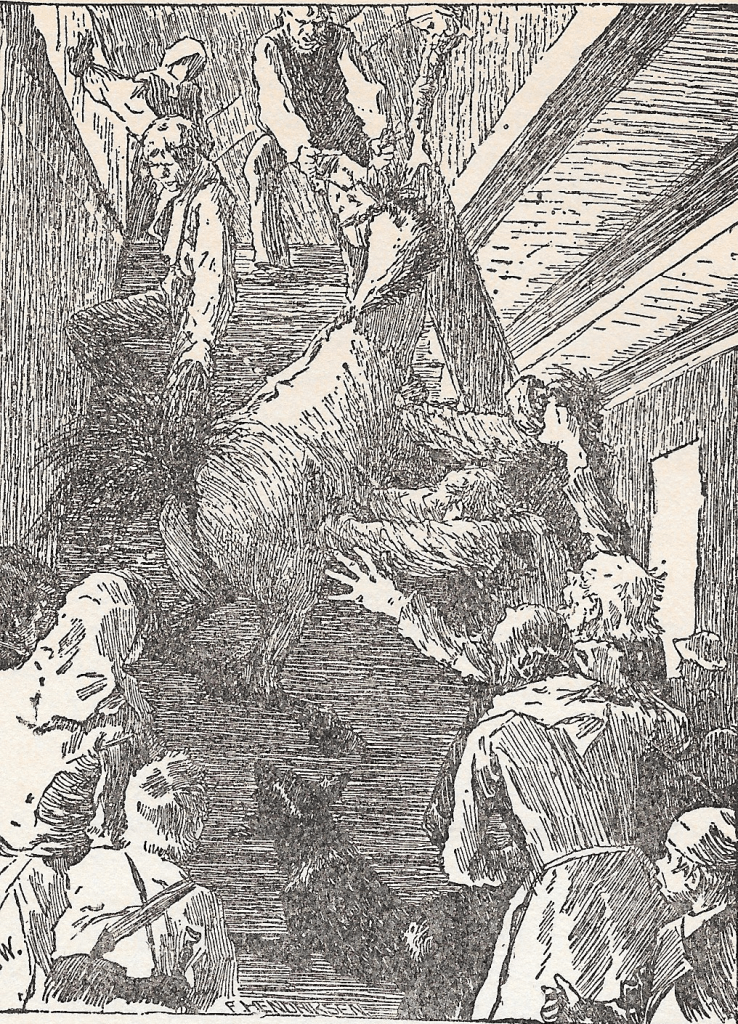

When the lad told the squire that “she” was waiting at the door, the squire informed the lad to take “her” upstairs and call for the women to dress the bride for the wedding and not forget the traditional wreath and crown. The lad’s hesitation merely annoyed the squire, who sent the lad off to do his bidding.

The lad, with great trouble and much manpower, got the horse into the dressing room where the women did the best they could to decorate the mare. Then the squire instructed them to bring “her” down to the parlor for the wedding.

Again, with much trouble, the lad overcame all obstacles, and in the end the horse trotted into the wedding, much to the chagrin of the squire and the amusement of the wedding guests. It is said the squire never went courting again.

“I do get that she tricked the squire,” Ulitima laughs, “but what was the fuss about? What is this marriage thing?”

Fairy Tale of the Month: January 2025 The Squire’s Bride – Part Two

About Marriage

“To answer that question, I will need some context,” I say. “Am I safe to assume you have children in your world?”

“Well, of course we have children! How else would we have a future?”

“Do you have children outside of marriage?” I ask rhetorically.

Ultima pauses before answering. “Yes. We have children. I don’t know what you are talking about when you say ‘marriage.’ Perforce, marriage has nothing to do with our children.”

I press on. “Do you have the word ‘marriage’ in your vocabulary?”

“Yes,” says Ultima cautiously, “but it is a technical term. For example, we marry tin with copper to make bronze.”

That is the opening I am looking for. “In my world, a man and a woman are married together, like tin and copper, to make children, our bronze. The union of tin and copper—a man and a woman—is permanent, like bronze. Well, at least, ideally,” I qualify.

Ultima blinks rapidly, then squints. “My turn to ask questions. Are you telling me that in your world you do not . . .” I see her struggling to find the right words, “have multiple partners?”

I sigh. “Are you familiar with the terms ‘etic’ and ‘emic?’”

“No.”

“To oversimplify, the etic is what people say they do or think they should do. The emic is what they actually do.

“In this case, the etic is that we have only one partner at a time, and it is best if we have that partner for life. In the emic, that does not always happen. Having multiple partners can be seen as scandalous.”

Ultima scratches her cheek. “You mean you’re not supposed to have multiple partners, and yet you all do?”

“Oh, not I. I was faithful to my wife.”

“Faithful,” Ultima echoes, contemplating the concept. “Exclusive?”

“You could say that,” I answer, “but see here, what is the role of fathers?”

“Why, to be our partners when we ask them to.”

“Do they help raise children?”

“Oh, goodness no. That’s between the women and the dragons, particularly the infant’s dragon.”

“How is the infant’s dragon chosen?”

That stops Ultima. “Chosen? No, they just appear, as they should.”

“You have no choice in the matter?” I ask.

“Why should I? It’s the infant’s dragon.”

That doesn’t make sense to me, but another thought enters my head.

“In our way of thinking,” I say, “you are married to your dragons rather than to the fathers of your children. They are your life partners.”

Ultima laughs. “That is an amusing way of thinking about it, but I won’t fault you.”

I don’t see the humor in what I said, but it is a marker of how much we don’t understand each other. I take one more shot.

“Despite the emic stuff,” I say, “the marriage between a man and a woman is considered as sacred. What is sacred for you?”

Ultima’s brows knit. “I think we are battling over the definition of words. Nonetheless, in my world chocolate is sacred.”

I will not disagree.

Fairy Tale of the Month: January 2025 The Squire’s Bride – Part Three

No Dragons

“Alright,” says Ultima, “I think I have a better grasp of this marriage thing. It comes up a lot in your fairy tales.”

“It does,” I agree. “What comes up in your fairy tales if marriage is not a thing?”

Ultima glances away from me in a show of embarrassment. “We don’t have fairy tales, which, I guess, is why I am fascinated with yours.”

“A world without fairy tales? Certainly you have myths and legends?” I am shocked.

Ultima ignores my question to present her own. “In our story, the maid does not want to marry the squire. I see there is an age difference, but she could be moving up in status. Is it the age difference that put a stop to it for her?”

I contemplate. “The story doesn’t say. She could be objecting to the age difference, or she may not find him attractive at any age, or she may simply not want to be in the state of wedlock.”

“Wedlock?” Ultima’s eyes widen.

“It is another name for marriage,” I say.

“As in locked into the state of being wed? No wonder she objects. She would be a prisoner!”

“No, no. You are not quite getting it,” I say, hoping she is not right. “Marriage is—well—complex.”

Ultima lets me wallow in my confusion and waits patiently for me to finish my answer.

“I won’t defend the state of marriage in my culture but cut to the chase of fairy-tale marriages. In the tales, marriage is a reward. Almost invariably—there is always an exception to the rule, and there may be an exception to that rule—in a fairy-tale marriage, one of them is of royalty and the other is marrying up. Even in stories like Beauty and the Beast, the Beast is actually an enchanted prince.

“In cases like The Goose Girl or Snow White, the heroine was of royalty, lost her status, but regains it through marriage. In either case, they marry up.

“Our story is one of those exceptions. A marriage is proposed but does not happen, with humorous results. The squire, at least, does not live happily ever after.”

Ultima nods with understanding. “That sounds to me,” she says, “like wish fulfillment by a lower class that one could rise from being a pauper to being a king or queen.”

“Exactly.”

“Is that a reasonable goal?”

“Well, no, not really, but the fairy tales are not meant to be guiding lights.”

“No, no, not guiding lights,” Ultima says thoughtfully. “More like flickering candles in the dark. The tales make some rather wild suggestions.

“You asked if we have myths and legends. We do, and we consider them part of our history. While I so enjoy your fairy tales, my world does not need them. Instead, we have the wisdom and counsel of dragons.

“Simply stated, you have fairy tales. We have dragons. My heart goes out to you for that lack from which you must suffer. A world without dragons, dear me.” Ultima shakes her head.

Your thoughts?