The Donkey

I had decided that I would not sulk around the house this year when my daughter, as is traditional, would whisk my Thalia away from me in February (school be damned) to visit her late husband’s relatives in Glasgow. Well, it has been three years, given the circumstances, since this visit was made. I did have a reprieve.

But now, Thalia is gone, and I rang up Duckworth to see if he was available for lunch. He, too, has been abandoned by his wife and children for a visit to her relatives, whom he cannot stand. He and I are compatriots.

We are sitting in Rock and Sole Plaice waiting for our meal. True, every pub in London has fish and chips on its menu. But here, there are nearly a dozen variations. Duckworth, adventurous soul that he is, ordered the calamari and chips. I stuck to the plaice, although tempted by the Proper King Prawns.

“Tell me,” says Duckworth as we wait. “What bizarre fairy tale have you stumbled across recently?”

“Well you should ask,” I say. “With Thalia gone, I contented myself last night by plunging into Grimm. I chanced upon a tale I had read before but taken little notice of. This time, it caught my curiosity.”

“I’m all ears,” Duckworth grins.

“Perhaps you should be,” I say. “Its about a donkey. In fact, it is called The Donkey.

A king and queen at long last have a child, but it is a donkey. The queen wants to drown it, but the king says if this is God’s will, it will inherit the throne.

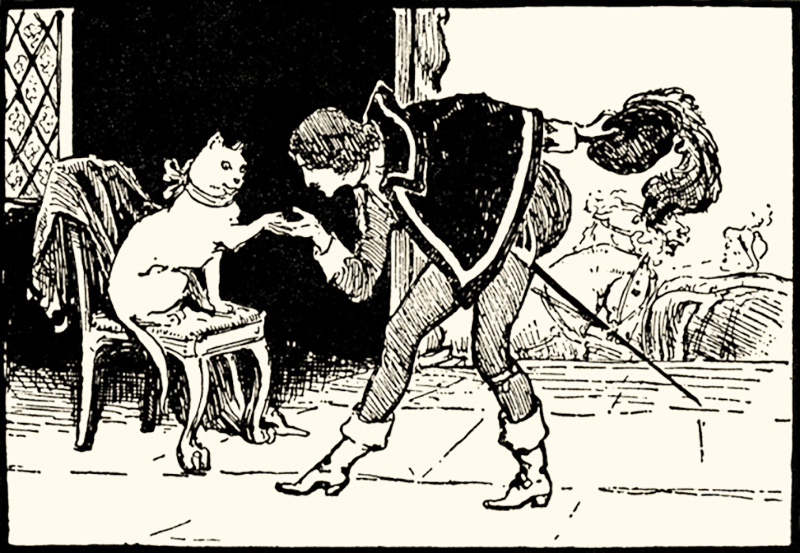

The donkey grows up with all the benefits of a prince. Being attracted to music, he learns to play the lute as well as his teacher, despite his hooves.

At length, he ventures into the world after seeing his reflection in still water and truly realizes he is, by all appearances, a donkey.

He travels to a distant kingdom, and there he asks for entrance into the castle as a guest. Being a donkey, his request is denied by the guard. The donkey sits down by the gate and plays his lute. The guard, amazed, reports this to the king. The king, entertained by the idea of a lute-playing donkey, invites the donkey into the castle.

The donkey refuses to eat with the servants or even the knights. Being of royal birth, he insists upon eating at the king’s table. The king, amused, agrees. The donkey’s manners are impeccable, and he is seated by the king’s lovely daughter.

As time goes on, the king becomes exceptionally fond of his “little donkey.” However, the donkey realizes the futility of his presence at this king’s court and asks leave to return to his home.

The king offers him gold and half his kingdom if he will stay, but this is not what the donkey wants. The king then offers his daughter in marriage. At that, the donkey agrees to stay.

That night, the wedding is held, but the king immediately has second thoughts and arranges that a servant hide himself in the bedchamber to assure that the donkey conducts himself properly.

When the donkey believes all is secure, he throws off his donkey skin and reveals his true, handsome self to his bride, who is delighted. In the morning, he returns to his donkey skin.

The servant reports to the king, who is amazed and wishes to see all this for himself. The servant advises that the king take the donkey skin and burn it, which the king does.

In the morning, the handsome prince cannot find his skin and tries to flee. The king waylays him and offers, again, half his kingdom if the prince stays. The prince relents.

Eventually, he inherits all of the kingdom, plus his own father’s kingdom, and lives out his life in splendor.

“Oh, really?” says Duckworth, shaking his head. “Way too easy.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: February 2024 The Donkey – Part Two

Donkey’s Skin

The meals arrive, and conversation halts as we sample our choices.

“‘Way too easy’ you say?” I comment after I decide I made the right menu choice.

“Well.” Duckworth sets down his fork. “As I understand story structure, be it literary or oral, there must be a crisis, a high point of tension, at the climax of the story.

“In our case, the prince cannot find his familiar donkey skin, tries to flee, and is stopped by the king, who offers him half the kingdom if he stays. The prince says, ‘What the hell. Why not?’

“This is not a crisis. There is nothing to lose but the curse of a donkey skin in return for half a kingdom! The stakes are not high.”

“I do agree,” I confess. “The end of the story falls flat. I feel the same way as you, but the earlier part of the story holds promise.”

“Such as?” Duckworth picks up his fork again to attack his meal.

“Well,” I contemplate, setting my fork down, “I am encouraged by the donkey’s father refusing to drown the poor thing, but rather giving him all the benefits of royal birth. The donkey takes to music and learns to play the lute, which should be impossible. This shows the reader or listener that there is more to this creature than being just a donkey.

“Perhaps my favorite part is when he sees his reflection in still water and sees himself as the rest of the world sees him. This is the point—in Hero’s Journey terms—when he crosses the threshold and ventures into the greater world to try, I suppose, to find himself. What he knows is inside him, and what he sees in the still water are two different things he needs to reconcile.”

“I’ll buy that,” says Duckworth, dipping a chip into the sauce. “Go on.”

“He passes two tests: getting into the castle by a show of his musical talent, and then getting to the king’s table by insisting on his rank. The king appears more amused by the donkey’s claim than convinced, but nonetheless, seats the donkey beside his daughter.

“However, in time, the donkey, despite his achievements, could see no way forward, especially concerning the princess. When he asks leave to return home, the king, to the donkey’s delight, offers him his daughter in marriage to tempt the donkey to stay.”

Duckworth raises his fork. “Isn’t that, ah . . .”

“Sexist?” I supply. “Well yes, but women were property back then, and back then was not so long ago, and don’t get me started on that or I will lose my point.”

Duckworth lowers his fork and applies it to his calamari.

“Where was I?” I continue. “Oh yes. In the bridal chamber he finally reveals his true identity to the princess and, I will suggest, to himself. But then, in the morning, he retreats back into his lesser, familiar form. It is only when the king destroys the donkey skin is he forced to accept himself in his true nature.”

“That does put the story in a new light for me.” Duckworth salutes me with his last chip before popping it into his mouth.

“What fascinates me,” I continue, “is the fairy-tale trope of the hero feeling he has to disguise himself for no apparent purpose. That bit I have never figured out.”

“Wait.” Duckworth’s eyes narrow. “This is not your typical line of argument. Who have you been talking to?”

He’s caught me.

“I had this same conversation last night with Melissa.”

“I thought so. She has much influence over you, you know.”

Picking up my fork, I say, “For the better, I hope.”

Fairy Tale of the Month: February 2024 – Part Three

A Stroll

Leaving the Rock & Sole Plaice by hopping into Duckworth’s Morris Minor, we make our way down to Victoria Embankment Gardens to walk off some of the calories we absorbed and to visit Cleopatra’s Needle, simply to have a destination.

As we walk down a gravel path, Duckworth asks, “So, why do you think the Grimms wrote this story?”

“That’s a hard question to answer, given that they did not write them and yet they did.”

“Sounds like an answer off to a wrong start,” Duckworth quips.

“Well, it’s simply that the Grimm brothers collected the stories from various sources, including variants, then wrote them up in a coherent fashion, trying not to stray too far from the originals, at least in the first edition, which they considered to be a scholarly work.

“Their purpose was to establish a ‘German Folk Voice’ in the context of the rising German nationalism. Remember, this was in 1812, when the Holy Roman Empire still held sway. There were only empires, no nations.”

We pass the erotic statue that graces the Arthur Sullivan Memorial. Arthur being of the famous operatic duo Gilbert and Sullivan.

Is that the definition of bad taste?

Duckworth glances sidelong at me. “I hear you leading to something amiss when you say, ‘at least in the first edition.’”

“Quite so. The Grimms quickly realized their larger audience was the children of bourgeois families. After the first edition, Wilhelm took over Kinder- und Hausmärchen, leaving Jacob to lead in their more scholarly works (a dictionary and a collection of Germanic mythology). There were six more editions of Kinder- und Hausmärchen; Wilhelm could not leave it alone.

“Wilhelm, in consideration of his Christian audience, eliminated most of the pagan references in the original stories and supplanted them with more Christian elements. Angels appeared in some of the rewritten versions, who had not haunted the tales before then.”

We now stroll beside the Thames. Duckworth returns to my earlier point. “They were seeking the ‘German Folk Voice’ you say?”

“Yes, which involved a bit of irony. A number of the better-known tales, like Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White, and Sleeping Beauty, the Grimms collected from a friend and neighbor, Marie Hassenpflug of a French Huguenot family. The daughters of another neighbor, the Wild family, also of Huguenot origin, supplied quite a few other tales. One of these girls, Wilhelm ended up marrying.”

“Oh my,” says Duckworth, “collecting tales was quite a different business in those days, was it not?”

Cleopatra’s Needle comes into view.

“The Grimms were not the ‘field’ folklore collectors that were to follow,” I continue, “but depended upon friends and acquaintances to gather their material. For example, Philipp Otto Runge. He was a German Romantic painter and color theorist—and an exquisite mind that passed away too young. He sent the Grimms two stories, The Fisherman and his Wife, and The Juniper Tree. When Wilhelm read these tales, he was much impressed by Runge’s ‘voice.’ Wilhelm patterned the collection’s style on Runge’s.”

“Well, now that we are here,” says Duckworth, “we can turn around and go back. I think we can spend a little time at Sullivan’s memorial.”

Good heavens!

Your thoughts?