Staying Afloat

There is something about the plunge of an oar into the water and the glide of the boat propelled by men’s muscles that is soothing to the soul. Duckworth and I have taken to the Isis, our upper part of the Thames, to do a bit of rowing before the weather becomes too brisk.

Duckworth always humors me by asking about what fairy tale I am delving into. I doubt he concerns himself with the tales outside of my presence. I am his sole source on the topic, and he humors me now.

“So . . .” He hardly needs to ask.

“A tale called Peter Bull,” I respond as we continue to pull on the oars.

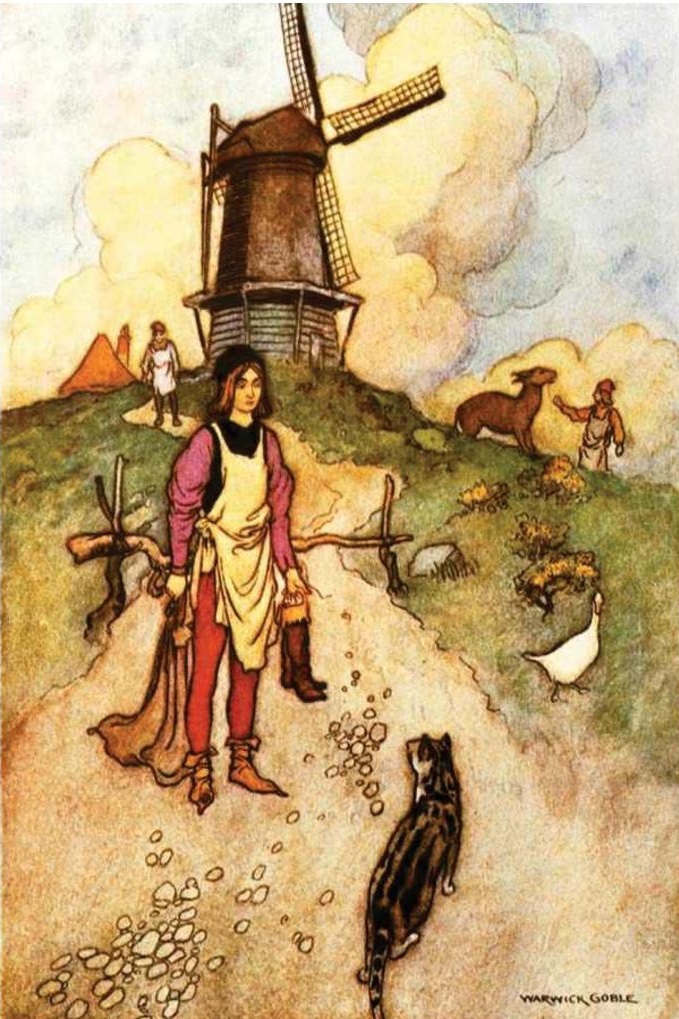

A well-to-do Danish farmer and his wife lived happily but for one thing. They had no children. Because of that, they became attached to one of their bull calves, which they named Peter. The husband speculated that perhaps the church clerk, known as an educated and clever man, might be able to teach Peter how to speak, and his wife agreed.

The clerk, seeing an opportunity, consented to educating Peter under certain conditions. First, the education must be done in secrecy, especially hidden from the priest, since it was forbidden. Second, there would be a cost because the books required to educate the calf were expensive.

Gleefully, the farmer turned Peter over to the clerk and gave him a hundred dalers. After a week, the farmer visited the clerk to see how things were going. The clerk reported that Peter was making progress, but the farmer could not see him. Peter loved the farmer and his wife so much, he would want to go back home and interrupt his learning. The farmer understood this and left another hundred dalers for the necessary books at the clerk’s request.

This sort of thing went on for some time. The visits from the farmer became less frequent in that they cost him a hundred dalers each time. Eventually, when the calf was fat enough, the clerk slaughtered it for a number of excellent veal meals.

“No, wait,” Duckworth exclaims. “Are you kidding?”

“Stay with me,” I say. “The tomfoolery gets worse.”

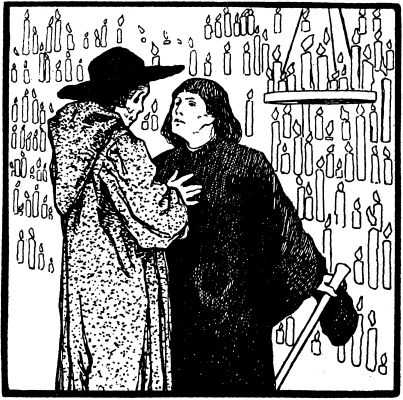

Soon after the clerk slaughtered the calf, he went to visit the farmer, declaring Peter’s education was complete and that Peter wished to return home. In fact, they had started out together, but the clerk returned home for his walking stick. Setting off again, he realized Peter had not waited for him, and the clerk asked the farmer if the calf hadn’t gotten there before him? They inquired around the neighborhood for the lost Peter, but it bore no results.

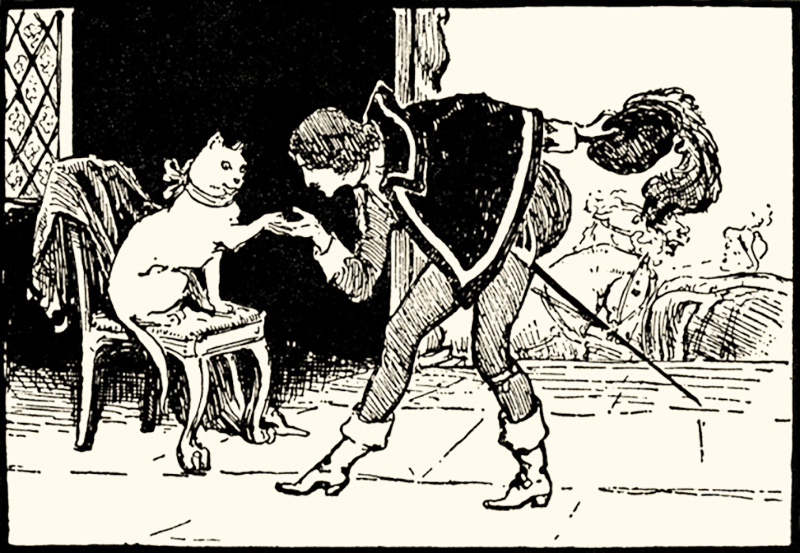

Sometime later, the clerk came across an article in a newspaper that referred to a Mr. Peter Bull, a young, struggling merchant. The clerk cut out the article and presented it to the farmer, suggesting that this might be their son. The farmer took off immediately for a few days’ journey, arriving at his destination early in the morning, invading poor Mr. Bull’s bedroom. Peter Bull was a bullish-looking fellow, and the farmer felt he recognized his Peter in him. Peter Bull dealt with the lunatic cautiously until he understood that the farmer intended to make him heir, at which point Peter warmed up to him and agreed to call him “father.”

In the end, the farmer sold his possessions, gave the clerk another two hundred dalers for his good services, and he and his wife moved in with the merchant, making him wealthy, and in return the merchant took good care of them for the rest of their happy lives.

Duckworth gives me a dubious glance, but he can’t suppress his grin.

Fairy Tale of the Month: November 2024 Peter Bull – Part Two

Correct Me

“Correct me if I’m wrong, but aren’t fairy tales supposed to have a moral?”

“I am happy to correct you, Duckworth. You are wrong.”

“Explain.”

“I will speculate that the notion that fairy tales should have a moral comes from two sources. First is Aesop, that admirable Greek slave, whose formula for storytelling did have a moral at the end. Second are the Grimm Brothers, who were appealing to a Protestant, bourgeois audience and therefore implied a moral at the end of many of their tales.

“But they were not as consistent as Aesop in moralizing. For example, one of my favorite Grimm tales is The Three Spinners. It is similar to their Rumpelstiltskin, with some significant differences.

“In the story, a mother, rather than admit that her daughter—although pretty—was a wastrel, declared the girl could spin flax into gold. The queen took the girl up to the castle, relieving the mother of a useless daughter. On pain of death, the girl was to spin rooms of flax into gold.

“Three ugly fairy women appear, and for two nights, accomplish the task for mere trinkets. On the third night of this endeavor, the poor girl runs out of trinkets. Then the fairies request she invite them to her wedding to the queen’s son, which they know will happen.

“This small request the girl remembered to make when the wedding plans were made. She described them as cousins. When the wedding feast began, the three ugly fairies entered the hall to the notice of everyone.

“The prince, the girl’s new husband, approached the fairy women, rather rudely, and asked about their deformities. One had a huge foot from running the treadle, the second a gargantuan thumb from rubbing the thread, and the third a large drooping lip from wetting the thread. The prince looked at the three women, then his beautiful bride, and declared she would never again spin flax.”

Duckworth drops his oars and applauds.

“And,” I continue, “I can think of another lacking-a-moral Grimm tale called The Master Thief, a Robinhood sort of figure who, on a dare, for example, steals the bedsheet of a lord during the night.”

“Clever,” remarks Duckworth.

“Yes, clever,” I say. “There is also The Clever Farmer’s Daughter, who wins a king because of her cleverness, loses him because of her cleverness, then wins him back again through cleverness.

“Ah, but then there is Clever Else, who is not so clever and fools herself into thinking she is not herself. Clever Hans doesn’t do any better, and neither do the characters in The Clever People. “

“I think I see a pattern emerging.” Duckworth grins at me. “You are suggested there are many stories in the Grimm collection with the themes of cleverness or its opposite, beside those with a moral.”

“I still have to mention The Clever Little Tailor, The Clever Servant, and Clever Gretel.

“Well, now you have,” he returned.

“But then there’s Doctor Know-It-All.”

“Enough!” Duckworth shook his head at me.

I guess I made my point.

Fairy Tale of the Month: November 2024 Peter Bull – Part Three

But Seriously

“But seriously, now,” Duckworth speaks after a short while, “you have pointed out to me that there are different kinds of fairy tales, but what makes a fairy tale a fairy tale?”

“Oh, you want me to pontificate, don’t you?”

“I want to see if you will run out of breath before we finish rowing,” Duckworth jests.

“Well,” I begin, “it comes out of the oral tradition along with its companions, myths and legends. That is another way of saying the oral tradition is not literary. Myths, legends, and fairy tales have been written down, but they do not have an author.”

“Wait,” Duckworth interrupts, “didn’t Hans Christian Andersen write fairy tales?”

“No, he did not. He wrote literary fairy tales; he made them up. He was the author. He borrowed from fairy-tale structure, which made them sound like fairy tales.

“But this is the point where distinctions get cloudy. The Brothers Grimm collected their fairy tales, often from secondary sources, and put them closer to literary standards than the material they collected. However, they did manage not to overstep the genré rules for these tales.”

“And those rules are, may I ask?”

I think Duckworth is actually interested.

“I will start with the observation that few characters have names. Typically, they are identified by their position—king, queen, youngest son, old soldier. Often, it is the minor characters that have names.

“Followed by the convention that descriptions are sparse. We are told little about how things look.

“Next, the tales are in the third-person objective. We never get inside the characters’ heads.

“Also, the tales are not dialog driven. Dialog is used to highlight parts of the story. There is more telling than showing. Showing is a wordier process than telling. Telling is succinct, as are the tales.

“There is a propensity for the number ‘three.’ For example, in The Goose Girl, we see three drops of blood. Later on in the story, there are three streams to cross and three passages through the dark gateway.

“Royalty has magical powers. This is always assumed, perhaps a reflection of the times.

“Animals can talk, and not simply animals talking to animals, but also animals talking to humans.

“Evil, of the magical sort, must be punished and good rewarded. Naughtiness and deception, as in the clever tales, not necessary so. Typically, evil is destroyed in rather graphic terms.

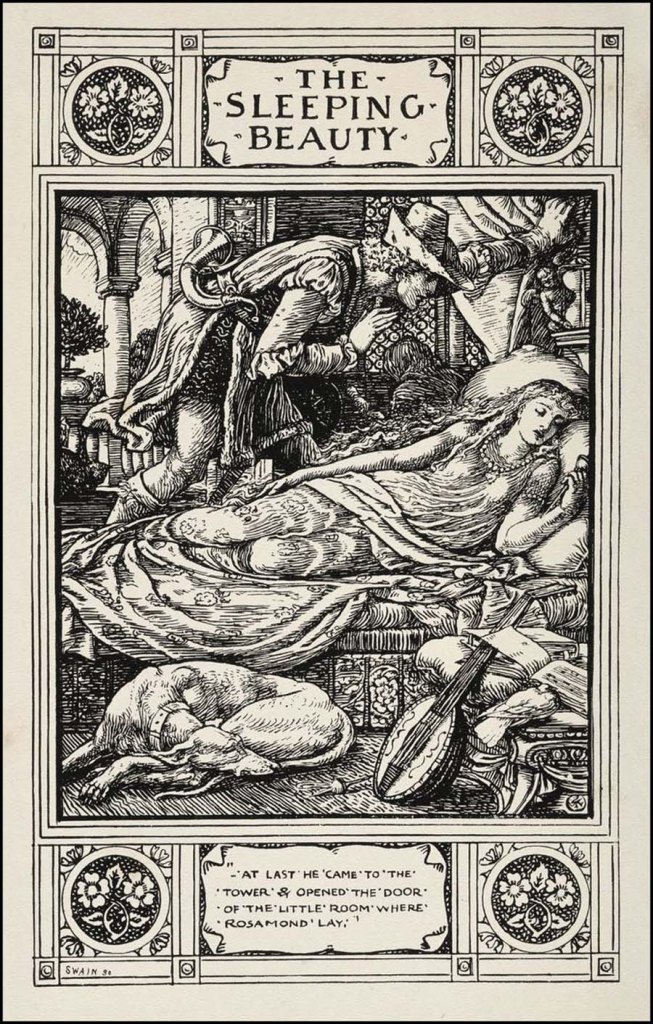

“The story usually ends happily. You can have a fairy tale without fairies, but happy endings are the rule. However, there are cautionary tales that do not end so happily.”

“That is a pretty extensive list,” Duckworth argues. “Can you make it more concise?”

“Yes. Fairy tales make bad literature. Really, they violate most of the rules of good literature. They stick to one POV, third-person objective. They ‘tell’ don’t ‘show.’ There are no beautiful, florid, or even accurate descriptions. And what is with the number ‘three’ all the time? It is more overused than ‘clever.’”

I get a chuckle from Duckworth.

“But seriously,” I say, “for me, the fairy tales are the stuff of dreams. Not those things we strive for, but those things that come to us, unbidden, in the night. There is a good reason for the tales to end happily. Theirs is the resolution that protects us from witches, demons, and the devil himself we encounter in the tales. All those things that make us uneasy while we sleep.”

Your thoughts?