What Tales Tell

Many a fairy tale can be found between the hard bindings of forgotten books, collections made over the past four centuries to keep those tales from disappearing entirely. Still, they lurk in the darkness of a closed book, rarely seeing light spilling across the open page.

They are the lucky ones.

The popular tales suffer a worse fate. Stories like “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves” have been rewritten by Disney, dissected by Bruno Bettelheim, paired with The Three Stooges (Yes, Snow White and the Three Stooges, 20th Century Fox, 1961), and recently recast by Universal, until the popular culture would hardly recognize the Grimm version.

The story starts with one of my favorite motifs, the wish for a child or lover who embodies the colors white, red, and black. Black enters the picture in various ways, sometimes as a crow, but in our story as the black ebony frame of the window, through which Snow White’s mother-to-be peers at drops of her own blood on the snow below. In this motif the red and white are, invariably, blood on the snow.

When the wished-for child is born, the mother dies. A year later the king remarries (and exits from the story as fathers are wont to do in Grimm tales). At the tender age of seven, Snow White is declared to be “a thousand times more fair” than her stepmother by the latter’s own magic mirror. The stepmother/queen’s all-consuming vanity leads her to instruct her huntsman to take Snow White into the woods and kill her, returning with the girl’s lungs and liver for the queen to consume.

The huntsman takes pity on Snow White and allows her to flee, assuming she will be killed by forest beasts, but at least not by his hand. He returns to the queen with the lungs and liver of a boar and exits the story, I will guess, through the same door as the king. Snow White ends up in the home of the seven dwarves, entering their abode through a process strikingly similar to that of Goldilocks’ entrance into the home of the three bears, but with more agreeable results.

As the dwarves warn their new housekeeper, it isn’t long before the queen’s mirror is telling her where to find Snow White: in the home of the seven dwarves, which is, interestingly, over seven mountains.

Three times the queen, in disguise, attempts to kill Snow White: with staylaces drawn so tight as to take the breath away, a poisoned comb put into the hair, and, finally, a poisoned apple.

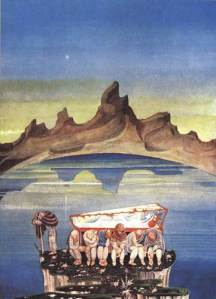

The dwarves thwart the first two attempts, but are at a loss to find the piece of apple in Snow White’s throat. When her beauty does not fade, they cannot bring themselves to bury her, but put her in a glass coffin over which one of them always stands guard. The glass coffin eventually is given as a gift to an admiring and romantic prince, who with a—no, not a kiss. It’s his bumbling servants, who nearly drop the glass coffin, but succeed in jolting the piece of apple from Snow White’s throat. She revives and is happily married to the prince. The stepmother/queen reluctantly comes to the wedding, where she in forced to dance in red-hot iron shoes until she drops down dead.

You know, all in all, the Disney version is a lot kinder and gentler. Universal’s rather graphic take is closer in spirit, if not in word, to the Grimms’. What might that say about Germany in 1815, America in 1937, and again in 2012? (I’ll skip 1961.)

Fairy Tale of the Month: June 2012 Snow White – Part Two

A Late-Night Snack

I am standing in front of my refrigerator, a box of Wheat Thins in hand, eyeing the plastic container of liver patè. I hold the door open, transfixed, my stomach growling, my thoughts leaping to the image of the evil queen thinking she is eating the lungs and liver of the innocent Snow White.

The Grimms never shied away from violence in their tales (much to the consternation of modern-day parents), particularly when it came as retribution for evil acts. Corporal punishment remained an acceptable norm well into the nineteenth century, fading as a practice in western society through the twentieth century. That the Grimms had their villains physically punished should not surprise us.

But cannibalism? The Grimms addressed a bourgeois audience. Certainly cannibalism did not enter into their day-to-day reality. I will guess the Queen’s request for Snow White’s lungs and liver came across as shocking to the Grimms’ first readers as it does today.

Fairy tales use cannibalism to exaggerate the evilness of the villain—no, I must correct myself, exaggerate the evilness of the villainess. In the tales, that crime is always committed by a woman.

In “Hansel and Gretel” a witch craves to eat Hansel. Looking farther afield, Baba Yaga is known to have an appetite for little children. (This cannibalism is not just a Grimm thing.) In “The Juniper Tree” the wife disguises her stepson’s murder by feeding the body to her husband.

In a variant on the cannibal theme, the heroine is falsely accused of eating her children. This comes up in “The Virgin Mary’s Child.” To punish a young queen for not confessing her sins, the Virgin takes away the queen’s children, after which the palace gossips accuse the queen of eating her offspring. Another example occurs in “The Six Swans” when the silent heroine’s children are stolen by the mother-in-law, who smears the girl’s lips with blood while she sleeps.

Never is the hero accused of eating his children, or consuming anyone else.

“Blue Beard” (Grimm) and “Mr. Fox” (English) get very close to, but are not accused of, eating their brides. All the remains appear to be in the forbidden room as keepsakes, hardly less abominable than the eating of human flesh, but, nevertheless, remains of the crime of murder.

There are other characters in fairy tales that like to feast on humans: wolves, giants, ogres, and trolls; but, to be cannibal, one must eat one’s own species.

I finally close the refrigerator door, now with the liver patè container in my hand. I read the ingredients; whose liver is this?

That the tales purport cannibalism to be a female trait casts an ominous shadow on the story landscape. What is being said? Why is this most monstrous act reserved for woman? I haven’t a clue, but I have lost my taste for patè. I think I’ll just eat one of those apples I bought at the farmers’ market from that old hag.

Then again, maybe I won’t.

Fairy Tale of the Month: June 2012 Snow White – Part Three

In the Mind’s Eye

Fairy tales deal in images. More precisely they get the listener to create their own images. The tales give us the barest, sketchiest outline of the setting and characters: once upon a time there lived a poor fisherman, or there lived a king with a lovely daughter. The listener fills in with their fisherman (does he carry a net or a fishing pole?) or their idea of a lovely daughter (raven black hair or hair of spun gold?).

On occasion the tales will give us something more complete, Snow White and her dwarves being one of these. We know from her mother’s wishes, she has hair black as ebony, skin white as snow, and lips as red as blood. Around her gather seven ugly, bearded, kindly dwarves. The contrast between her and her companions is so engaging it fires the imagination.

It fired the imaginations of the Disney animators and writers, who, perhaps to our disadvantage, supplied us with all the details of that image, including the dwarves’ names (Sneezy, Sleepy, Dopey, Doc, Happy, Bashful, and Grumpy, just to review), supplanting anything we might have come up with.

This image of Snow White and the dwarves has become so familiar that we tend to forget one of its non-traits. The seven dwarves do not constitute a motif.

There is no mention of dwarves in the Snow White and the Seven Dwarves variants (Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 709) listed on D. L. Ashiman’s very useful site.

One of the variants on Ashiman’s list is “Maria, the Wicked Stepmother, and the Seven Robbers” (Italy). Maria, in Hansel and Gretel fashion, avoids her stepmother’s first attempt to abandon her in the forest, but ends up in the home of seven robbers after the second try. Like the dwarves, the seven robbers assist the poor girl, but the stepmother is not done with her, and Maria turns up in a coffin to be found by a king.

In another Italian variant on Ashiman’s list, “The Crystal Casket,” our heroine, Ermellina, falls from grace in a manner similar to Grimm’s “Three Forest Gnomes” until rescued by an eagle who deposits her among helpful fairies (number of which is not given.) Despite the fairies’ warnings, the stepmother has her way, and as the title suggests, Ermellina is confined to the ubiquitous coffin until rescued.

“The Young Slave” (Italy again, via Giambattista Basile) has a strange variation on the Sleeping Beauty motif at the start of the tale, but has no collection of benevolent helpers anywhere in sight.

I want to say the seven dwarves appear to be unique, and exist nowhere else in the story realm. Alas, it is not true. Ashiman, at the bottom of his list, gives us a link to “The Death of the Seven Dwarves” (Switzerland). In this tale a pretty peasant girl, seeking shelter for the night, comes to the home of seven dwarves, who live on the edge of the Black Forest. They grant her entree, but, when an old woman shows up requesting the same, the girl answers the door explaining that the seven dwarves have only seven beds and there is no room for more sleepers. The old woman does the math and accuses her of being a slut. Enraged, the old woman returns that night with two men who break down the door, murder the dwarves, and burn down their house. What happens to the pretty peasant girl is not stated.

I didn’t start to write this blog post to malign the Swiss, but perhaps they had better stick to watches, cheese, and neutrality, and leave fairy tales to abler hands.

Your thoughts?

PS. Ashiman also listed “Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree” (Scotland) as a variant. It differs substantially from the other variants (no coffin), and is worthy of my time and its own blog post.

Anne Anderson

Anne Anderson