Tapestry (c. 1385)

Tapestry (c. 1385)

A Reading

I attend Melissa’s first “Open Reading” at her bookstore. I thought it a nice idea. Participants are given ten minutes to read a favorite passage. I invited Augustus and Duckworth, who obligingly show up. Melissa, Thalia, and I, along with two old women make up our paltry crowd.

Melissa asks me to start us off. I read Arthur in the Cave from The Welsh Fairy Book, by W. Jenkyn Thomas.

A Welshman, having sold his cattle in London at a good price, tarries about the shops on London Bridge—a thing that was before the Great Fire—when a strange man approaches him asking, “Where did you cut your hazel staff?” the staff being any drover’s necessary possession.

The Welshman is reluctant to talk to the stranger, but the man persists, revealing there is wealth to be gained in the prospect. They travel to Craig y Dinas in Wales, to the spot where the drover cut his staff. They dig until they come to a large flat stone. Prying it up, they expose a stairway descending into depths below. The drover follows the man, whom he has decided is a sorcerer.

At the bottom, beyond a door, they come across a bell.

“Do not touch that bell,” says the sorcerer, “or it will be all over with us both.”

Beyond the bell lay King Arthur’s court, asleep. A thousand knights in armor, ready for combat. Around a table, slumbering, sit the nobles of the court and King Arthur himself, Excalibur at his side.

“Are they asleep?” the Welshman asks, a man not beyond stating the obvious.

“Yes, each and all of them,” answers the sorcerer, “but if you touch yonder bell, they will all awake.”

The sorcerer’s intent is to steal some of the wealth lying around the cave, which they do, but the drover desires to see the court beyond their sleep state and rings the bell.

The court stirs, but King Arthur realizes their time has not yet come.

“My warriors,” says King Arthur, “the day has not come when the black eagle and the golden eagle shall go to war. It is only a seeker after gold who has rung the bell. Sleep on, my warriors, the morn of Wales has not yet dawned.”

The two thieves escape with their wealth and their lives, but the Welshman can never again find the spot where he cut his staff, try though he does.

My friends nod, knowingly. The two old ladies are perplexed by my choice of something not literary. I take it they are easily scandalized.

My companions’ readings are literary, even Augustus’s. I don’t really listen. The two old ladies read from their favorite romance authors. Thalia reads The Singing Bones, which the old ladies accept coming from a child. I am proud of Thalia, holding her own in such company.

As our literary disaster is breaking up, Melissa whispers to me, “Can we meet with Mr. Thomas at our bench?”

I note the plural “our” and am pleased.

“I think so,” I say.

Fairy Tale of the Month: July 2016 Arthur in the Cave – Part Two

W. Jenkyn Thomas, National Library of Wales

W. Jenkyn Thomas, National Library of Wales

I notice Miss Cox’s tiger lilies are in full bloom, while those in my yard are putting forth their last efforts. Melissa sits, rather at attention, on the bench, her eyes directed toward the garden gate. I know she is still reckoning with her amazement at speaking with past authors. Meeting Jenkyn

Mr. Thomas is prompt in arrival, his movements businesslike, with the air of a man intent on taking care of whatever question is at hand.

“Sir,” he addresses me. I, with a nod, defer to Melissa.

“Madam, whom have I the honor of addressing?”

“Melissa Serious, and I have perhaps a peculiar question concerning your inclusion of an Arthurian tale in a Welsh fairy-tale collection. I have always thought of Arthur as an English hero.”

“Oh, the book.” Jenkyn’s businesslike manner melts with a laugh. “I assumed you were a member of the School Committee Association come to raise me from my rest over some procedural issue. They were relentless.

“Arthur, you say. I included him because we Welshmen consider him one of us.”

Melissa’s smile encourages him to go on.

“I took my cue from the Mabinogion. There are a number of Arthurian tales in the Mabinogion, which is that revered collection of Welsh legends. Note too, if Arthur is buried at Glastonbury, it is only across Bristol Bay from Wales.

“The Breton, Welsh, and Celtic histories and cultures are intertwined. Arthur, Pryderi, Rhiannon, and Branwen (not forgetting the Roman emperor Magnus Maximus) inhabit the pages of the Mabinogion.”

Jenkyn’s eyes take on a devilish glint. “Did you know pigs come from hell?”

“Pardon?” Melissa raises an eyebrow.

Jenkyn smiles. “According to the Mabinogion, King Arawn of Annwn, the underworld, gave to Pryderi, king of Dyfed, a new beast not known to them before. Unfortunately, it caused a war with the kingdom of Gwynedd when their king, Gwydyon, stole some of the swine.”

“Royal pig rustlers?” Melissa looks dubious.

“Something of a sport. The Celts were fond of stealing cattle from each other as well, and fighting to the death over it. Nor were they beyond stealing each other’s wives. A fun, if violent, bunch.”

“Is Arthur in the Cave also part of the Mabinogion?”

“No, not at all. I drew all the stories in The Welsh Fairy Book from dusty, scholarly tomes in which they were buried. I was only a few years into being headmaster at Hackney Downs when I noticed books of fairy tales were popular among the students. We were replacing them in our library with some frequency. But these books were, perforce, tales from other nations, Wales not having a handy collection of its own. I fixed that.”

Spotting the lemonade and glasses that Miss Cox has set out, I pour for the three of us. Handing Jenkyn his glass, I ask my own question.

“Our tale has Arthur and his court asleep in Wales at Craig y Dinas—The Rock of the Fortress—instead of Glastonbury?”

“Yes, it’s a limestone promontory near Neath, quite scenic, around which are a number of caves, one of them called Arthur’s Cave. Somewhere in its depth, Arthur and his thousand knights are sleeping, to be awakened when Britain needs to be saved. An appropriate place for the king to stay, although I think there are a half dozen sites around the United Kingdom making the same claim.”

Jenkyn raises his glass in a salute and takes a sip.

Fairy Tale of the Month: July 2016 Arthur in the Cave – Part three

John Garrick

John Garrick

Arthur’s Return

“Why would the Welsh want to have the British saved?” asks Melissa.

“It depends on one’s definition of Britain. The medieval Welsh felt Britain could be saved if the English and Normans were driven out,” says Jenkyns.

“Ahh, I see,” Melissa starts on her lemonade.

“Arthur was in that odd position of being claimed by the Celtic people, as well as the English and Norman royalty. Even the French Plantagenets made a bid for him.

“The belief in ‘Arthur’s Return,’” Jenkyn continues, “is not simply a Welsh thing. It is shared by Cornishmen, Bretons, and Scots, anyone with Celtic roots.”

“I take it then,” Melissa says between sips, “Arthur may be buried at Glastonbury, asleep at Craig y Dinas, or recovering on the Isle of Avalon.”

“Oh, it is worse than that. Besides the numerous British claims of a resting place, the Sicilians make a claim for Mount Etna. Avalon has been placed in the Mediterranean, somewhere near India, and even in the Otherworld.”

Jenkyn drains his glass and goes on.

“But Arthur does not own the ‘Sleeping Hero’ status. There are stories about our own Welsh king, Bran the Blessed, also slumbering beneath the earth, as well as Ireland’s Fin McCool, the renowned Finnian king. There are lots of other kings, including Frederick Barbarossa and Charlemagne; a good contingent of Roman emperors; and one or two saints, all slumbering and waiting.

“The first record of these sleeping heroes is an unnamed British deity mentioned in passing by Plutarch.”

“Plutarch? That puts the idea of the ‘Sleeping Hero’ into the first century,” Melissa notes.

“Yes,” says Jenkyn, “yet the folk tradition is not done with Arthur. It also has him not resting at all. In some parts of England he leads the “Wild Hunt.”

“The Wild Hunt?” I say. “I thought that the realm of the fairy folk.”

“Not exclusively. For example, in South Cadbury—not that far from Glastonbury—on stormy winter nights, the howling of the wind becomes the baying of Arthur’s hounds, or the sound of bugles, and only the glint of the horses’ silver shoes can be seen. They call it “Arthur’s Hunting Causeway.”

“Buried, resting, and riding,” Melissa muses.

“Oh, and still, tradition is not done with Arthur. It has transformed him into a bird.”

“Dear me,” I say.

“Sometimes Arthur is a crow, forever flying about, or sometimes a raven, in particular a Cornish Chough. Then, again, I have read reference to him as a puffin, and another time as a butterfly—that last not being a bird, of course.”

“There’s no end to it.” I shake my head.

Melissa slowly lifts a finger in the air. “Now that you have explained it, I think what I like about Arthur in the Cave is not the story so much as the lingering sense of hope for the Welsh that they have a hero who will be there when he is truly needed.”

“And that, my dear, is why the tale is in the book.”

Your thoughts?

PS. Miss Cox’s lemonade is especially good. You should try some.

Hohle Fels Flute

Hohle Fels Flute

Elizabeth Sonrel

Elizabeth Sonrel Frank Cadogan Cowper

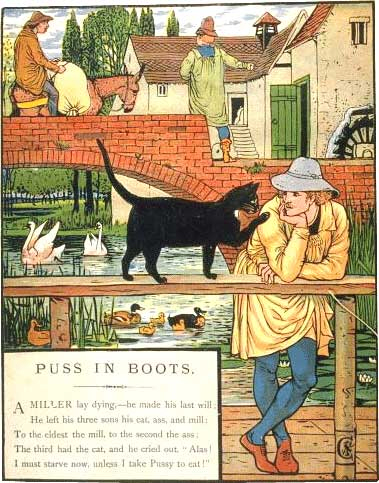

Frank Cadogan Cowper Walter Crane

Walter Crane Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer George Percy Jacomb-Hood

George Percy Jacomb-Hood From a Grimms’ edition

From a Grimms’ edition From 15th Century manuscript

From 15th Century manuscript Wild Man from a bestiary.

Wild Man from a bestiary.

Willy Pogány

Willy Pogány Willy Pogány

Willy Pogány John B. Gruelle

John B. Gruelle Traditional Jewish Hat

Traditional Jewish Hat